Hopper comes to life in this surreal yet strikingly “real” journey from Belgian developer Thomas Waterzooi

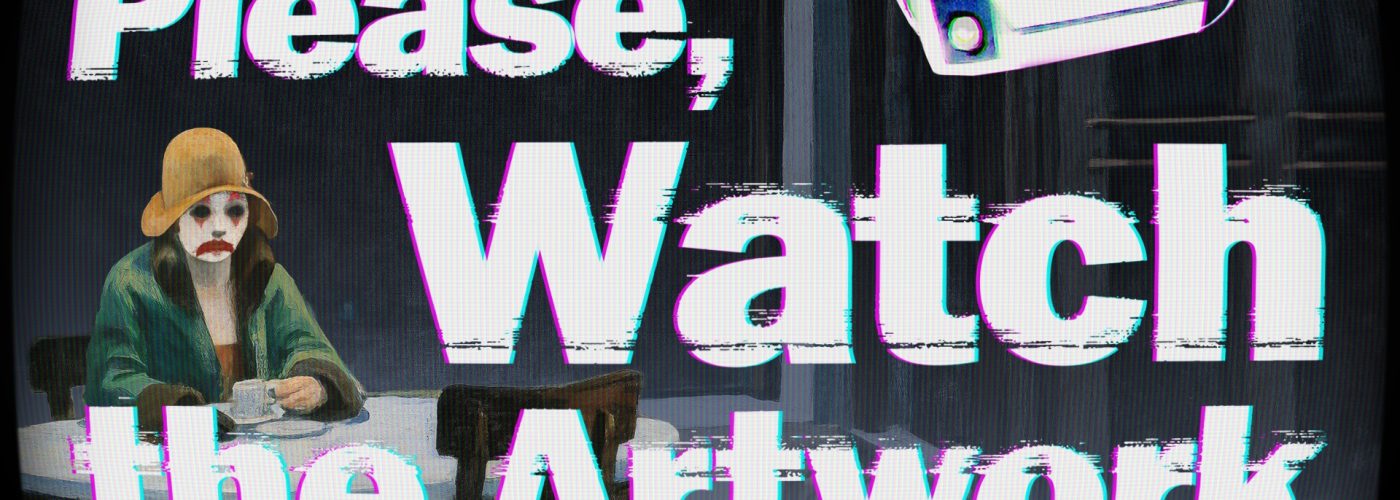

After Mondrian and Ensor, Thomas Waterzooi returns with a new aesthetic experiment: Please, Watch the Artwork — a demo that turns Edward Hopper’s American Realism into a game of observation suspended between art and unease.

The idea feels simple but deeply unsettling: you play as a night guard at the MaMA — the Museum of Animated Modern Art. Your job? Watch the paintings and report any anomalies, from midnight to six in the morning.

The paintings change. Slowly. Silently. As if they were alive.

It’s a Night at the Museum stripped of its Hollywood cheer. No talking statues or wild adventures here — just empty rooms, nostalgic noises, and figures barely moving inside their frames.

Because paintings, like the staircases at Hogwarts, love to change.

Guardian of the Absurd

The gameplay in Please, Watch the Artwork reshapes the formula of surveillance games like I’m on Observation Duty. The goal is to spot differences, click the anomaly, and report its type.

At first, it feels relaxing — until the silence of the museum starts to weigh on you, and the endless repetition of the same scenes begins to blur your sense of reality.

The atmosphere breathes through realistic ambient sounds: birds chirping, a faint sob, the echo of waves. No soundtrack — just environments inhaling and exhaling inside and outside the frames.

What begins as calm slowly morphs into paranoia. You catch yourself holding your breath, searching for a detail that doesn’t belong. And when you find it, you can’t tell if it was ever really there.

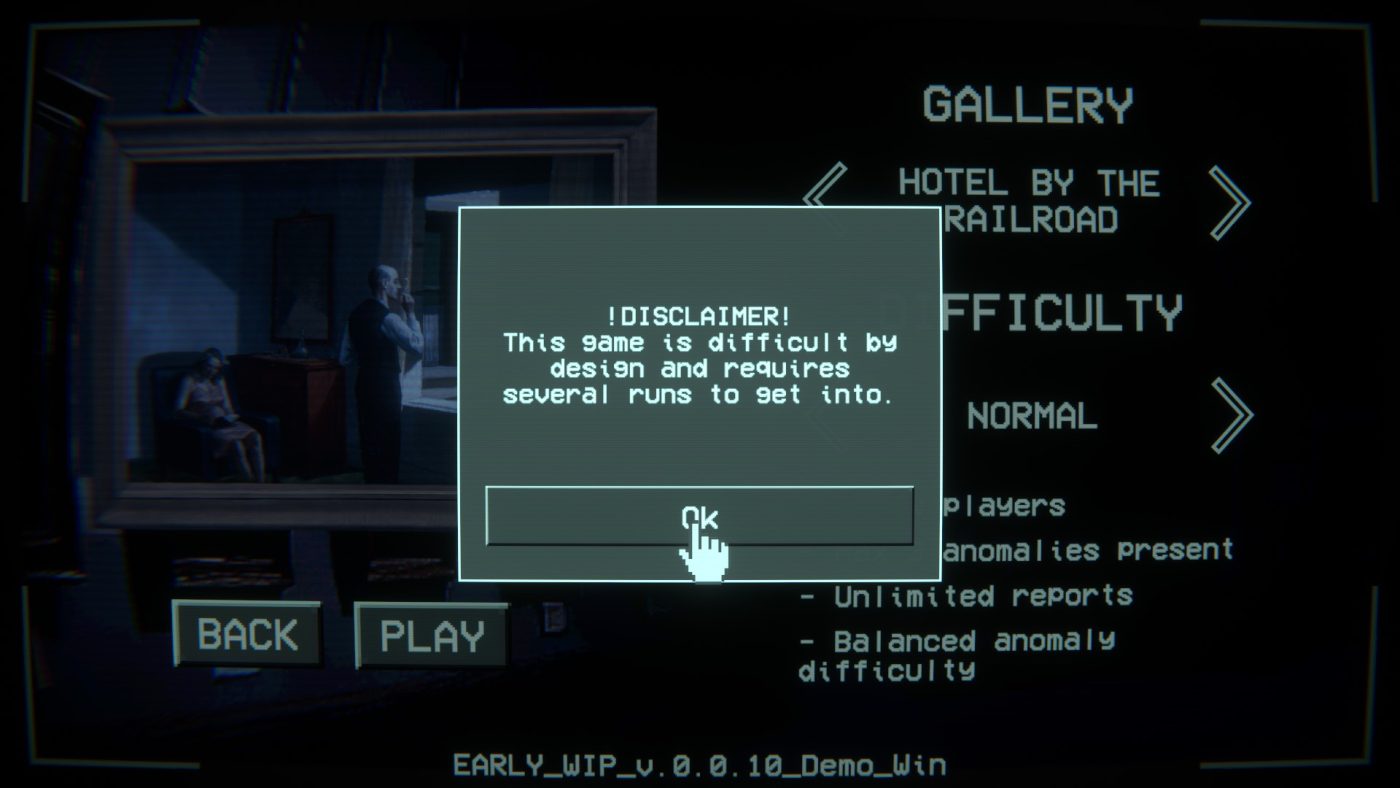

The demo offers a medium-to-high level of challenge. Anomalies appear at random, some almost invisible. Sometimes the line between an “extra object” and an “intruder” fades, but that’s part of the experience — mistakes feed the narrative.

The easy mode, reserved for the full release, is missing here, yet the pacing remains well balanced. The experience doesn’t punish you, even when it feels merciless, guiding you through a hypnotic slowness.

A disclaimer at the beginning warns of the countless firings you’ll face — and it doesn’t lie.

Still, understanding why you failed would help; not knowing what went wrong can be frustrating.

Loneliness Within the Frame

Every Waterzooi game opens a dialogue with an artist. After Mondrian and Ensor — the protagonists of Please, Touch the Artwork and Please, Touch the Artwork 2 — the focus now turns to Edward Hopper, painter of emotional distance and urban solitude.

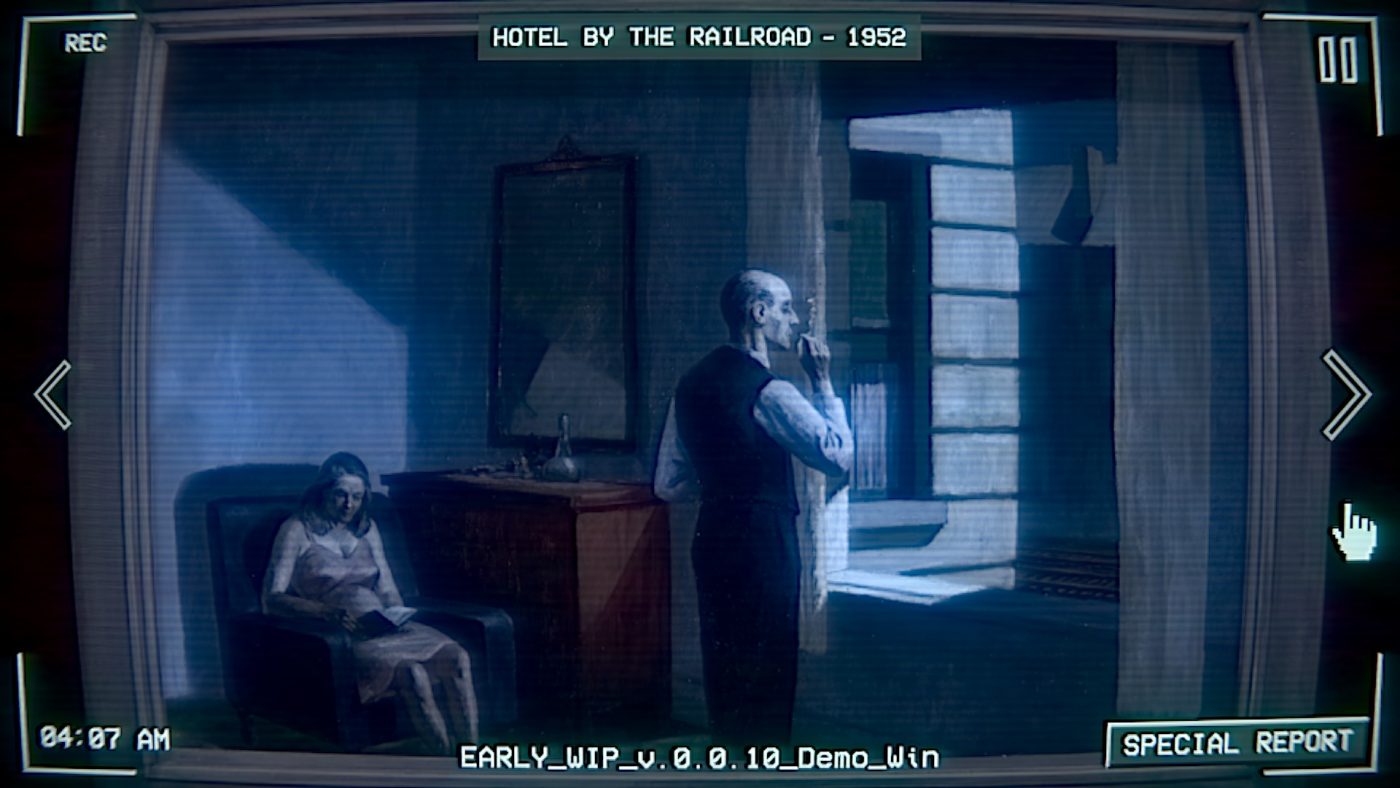

His figures — women by windows, men in late-night bars, silent couples in hotel rooms — live in suspended time, defined by waiting and disconnection.

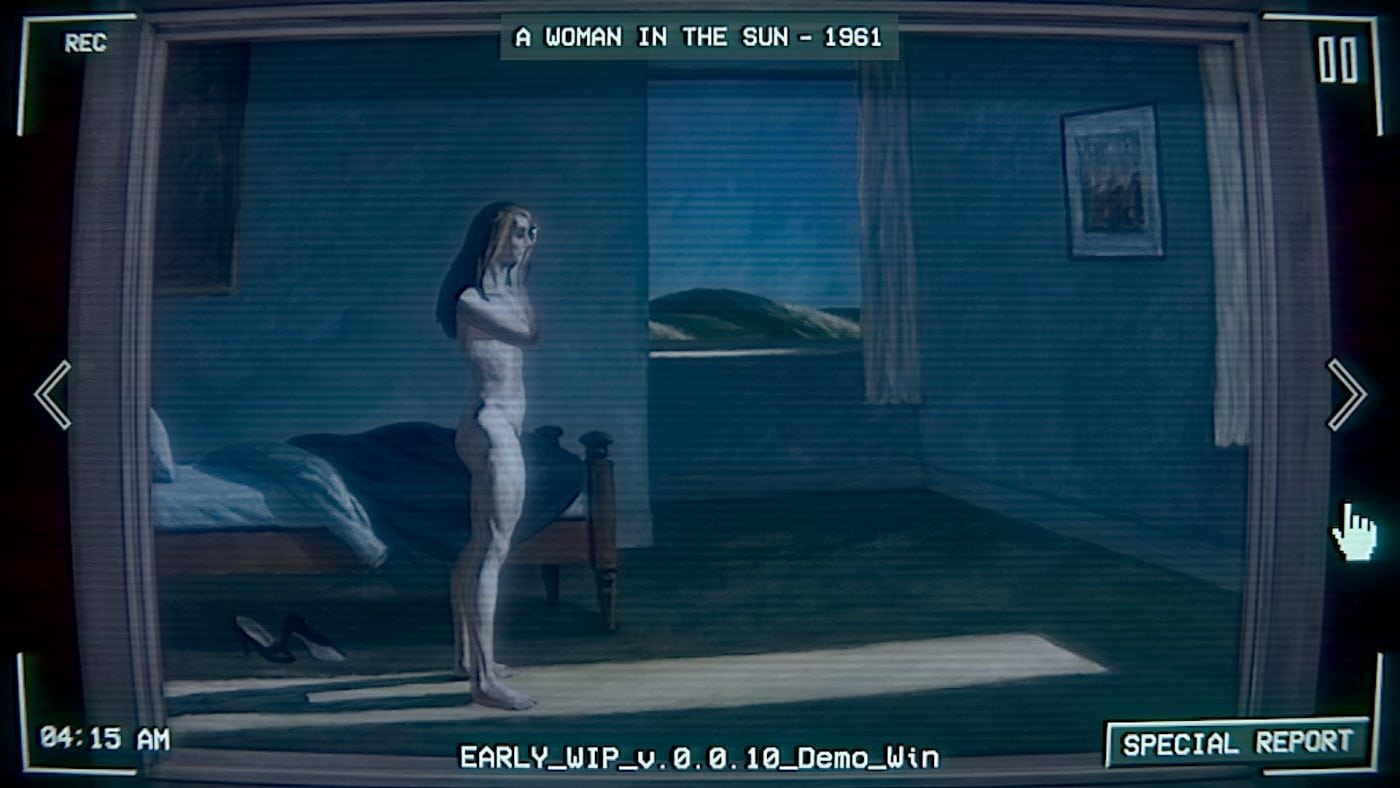

In Please, Watch the Artwork, those static worlds start moving. The demo features several of Hopper’s key works:

- A Woman in the Sun (1961) — a nude woman smoking beside an unmade bed. The morning calm invites us to imagine what happened before, a cathartic glimpse into aftermath.

- Eleven A.M. (1926) — a young woman sits by a window, watching, waiting, maybe thinking.

- Hotel Room (1931) — a quiet tragedy: a woman, head bowed, holding a letter in her hands.

- Rooms by the Sea (1951) — no figures, only light, sea, and a white wall. Peace and unease coexist in fragile balance.

- Hotel by a Railroad (1952) — a domestic tension that says everything without words.

- Morning in the Sun (1952) — among Hopper’s most iconic works, centered on solitude and introspection.

Waterzooi doesn’t betray Hopper — he expands him.

He adds motion where there was only stillness, and with it, he plants doubt. You can’t tell anymore if you’re seeing something real or if something disturbing is creeping in.

As if the melancholy in Hopper’s characters had always been a warning — now, at last, it’s taking shape.

The Clown That Haunts Dreams

Then comes the sad clown, drifting from painting to painting like an emotional virus.

A figure halfway between comic and uncanny, spreading melancholy through every canvas. This grotesque element is pure Waterzooi — the forced smile that exposes the fragility of both the game and its observer.

His works always carry this dual register: irony brushing against absurdity, and melancholy that clings to your skin.

No monsters, no jumpscares — yet Please, Watch the Artwork still manages to disturb, to slip unease under your skin.

It’s a cozy game that makes you feel watched, a calming experience that leaves you strangely unsettled.

And that’s exactly its strength: as with his previous titles, Waterzooi forces us to truly look.

A New Layer of Storytelling

Thomas Waterzooi’s talent lies in creating new narrative layers.

He doesn’t use video games to represent art — he makes art react.

In Please, Watch the Artwork, every movement, every sound, every subtle visual shift becomes a story.

It doesn’t tell; it suggests. It lets you fill Hopper’s silences with your own anxiety or curiosity.

Even mistakes play a role. You misreport an anomaly, hesitate too long, click too late — and time moves on, lights flicker out, the city outside falls silent.

Everything feels random, yet nothing feels meaningless. As if the museum itself were playing with you.

Conclusion

With Please, Watch the Artwork, Thomas Waterzooi reaffirms his ability to turn art into interactive experiences that are poetic, grotesque, and profoundly human.

The demo, though brief, already shows remarkable stylistic maturity and an impressive focus on visual and sound design.

It’s not a game about adrenaline — it’s a game about presence. It asks you to stop, to observe, to listen.

A truly original and striking way to step into the suspended world of paintings — and a compelling invitation to explore these extraordinary expressions of international culture.

If you want to know more:

Please, Watch the Artwork Official Website