Another masterpiece by Danish Playdead, and another lonely and abandoned boy forced to suffer a series of sadistic deaths

Inside is a puzzle platform game with 2.5D gameplay whose development and publication are the responsibility of the Danish geniuses of Playdead, already known for the unforgettable Limbo. Released in 2016 for PlayStation 4, Xbox One and Microsoft Windows, Inside has subsequently seen the light also for iOS in December 2017 and Nintendo Switch in June 2018. In June 2020 came out a version for macOS.

We are in an apparently dystopian context in which a little boy will have to undertake a journey through deadly dangers, solving rather elaborate puzzles.

HOW BRAVE ARE THESE DEFENSELESS CHILDREN?

Here, too, as in Limbo, the boy protagonist begins his journey through a forest. It gets dark, you can only hear the sound of his footsteps on the foliage, then, suddenly, he is near a departing truck, and the boy crouches down so as not to be seen.

Shortly after, men with torches force the boy to proceed with caution so as not to be discovered and from here we begin to understand that this young protagonist is either on the run from something, or is in any case well aware of the threat from which he tries to stay away.

Barbed wire, guard dogs, patrolling cars equipped with spotlights and so on are a clear sign that we are in a dangerous environment, and this boy, alone and abandoned, seems to be surrounded by countless threats.

Once out of the forest, after escaping from the guards, the young anonymous protagonist finds himself in a corn field from which he will finally arrive in an abandoned area that appears to be a farm. The rain falls straight and copious and the boy, determined to get out of this disturbing situation, proceeds without fear, but always with extreme caution.

The first watershed moment occurs at this point: after witnessing the escape of pigs frightened by parasitic worms, the boy will find a strange helmet which, once put on, will turn out to be a powerful tool for the control of lifeless bodies, used as workforce. As the protagonist continues his escape, through these apparently abandoned and gloomy places, the bodies controlled by the helmet will become useful for finding various tricks to be able to continue along the path.

THE MIND’S POWER AND THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTROLLING IT

Control strategies, mysterious machinery and not very reassuring plans are now the clear sign of the existence of an organization from which we must at least free ourselves. I don’t say defeat, because even in this case, as in Limbo, the protagonist doesn’t seem to have any other skills than the logical ability to find ingenious solutions for overcoming various obstacles.

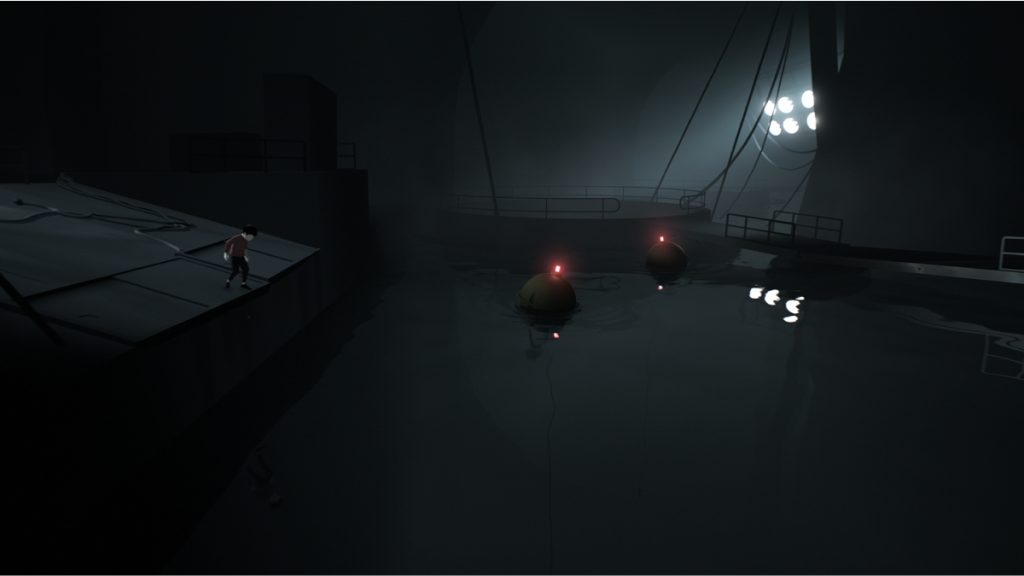

After a long underwater exploration, driving a small and bizarre spherical submarine, and then swimming, thanks to a device donated by a creature that will allow the boy to breathe, we will arrive in a huge place full of structures partly submerged by water.

We have therefore arrived at the heart of the matter: the existence of a series of secret laboratories in which scientists carry out underwater experiments on the poor bodies of those who no longer seem to be even individuals, if not for their anthropomorphic appearance.

The boy, followed by an increasingly conspicuous number of these bodies that partly help him and partly seem to be able to achieve freedom thanks to him (this aspect of Inside reminded me a lot of Oddworld, but with a definitely different atmosphere), reaches a spherical chamber inside which is a deformed creature that seems to be made up of many bodies: the Huddle.

The boy will free the Huddle, which will engulf it in its shapeless mass and subsequently, in an attempt to escape, running and rolling on the limbs protruding from all sides, will overwhelm and kill everything in its way.

There are two endings. After the surviving scientists capture the Huddle, it again manages to escape and in the first finale, it goes down a hill in the forest and stops on a grassy coast bathed in light.

In the second ending, the alternative one, which will happen if the boy deactivates the balls of light hidden in the various bunkers during the game, we will have access to a new area where there is a computer bank and a mind control helmet, connected to a plug. By pulling the plug, the boy will transform himself into one of many inanimate bodies.

THE ETERNAL AMBIVALENCE OF SCIENCE

Just like for Limbo, also in this case Playdead did not want to give any explanation, leaving the users the opportunity to find one.

So what’s yours? The theory of the cruel experiment carried out for the usual nefarious and profitable purposes, the metaphor of the disease, according to which the boy, distinguishable thanks to that touch of red in the shirt he wears and who, presumably, would represent a virus, or the exact opposite, that the boy embodies the cure for the disease?

There are also those who think the Huddle is the real controlling subject, which pushed the young boy to make the perilous journey in order to get free.

Once again, it is a matter of allowing one’s imagination to run wild and, all in all, there are many elements to create a plausible theory, just as one could live the gaming experience without asking who knows how many questions, a little like I did. I enjoyed it without looking too much for meaning, because, in my opinion, it is precisely the visual and gaming experience that makes this title another undisputed masterpiece.

AESTHETIC SYNTHESIS AS AN ABSOLUTELY EFFECTIVE ARTISTIC FORM

The aesthetic style of Playdead is now unmistakable: monochromes, shapes reduced to the bone, dark and mysterious atmospheres, evident references to a certain type of cinema, such as the German expressionist one in the case of Limbo. In Inside, however, there is an addition of elements to make it more three-dimensional and above all emblematic.

In fact, unlike Limbo, here there are some chromatic elements that serve to give a sense of depth to the locations, to highlight areas or, in the most striking cases such as the protagonist’s red shirt or the blood present following the usual super bloody dead, to create symbolisms.

Concept artist Morten Bramsen (yes, always him), created the Huddle in 2010. Based on his initial design, animator Andreas Normand Grøntved, as well as the rest of the art team, took inspiration for the whole visual nature, and the art style of the game.

It is curious to know that for the Huddle, Grøntved got the idea from the demonic form of the boar god of Princess Mononoke, Nago. He then developed the initial animations using what he himself called “Huddle Potato”, which, thanks to the simplified geometries of the model, was able to demonstrate how the being would move and interact with the environment.

While most other game animations had a combination of preset skeletal movements along with the physics engine, the Huddle had to be animated almost entirely from a custom physics model developed by Thomas Krog and implemented by Lasse Jon Fulgsang Pedersen, Søren Trautner Madsen and Mikkel Bøgeskov Svendsen. This model uses a 26-body simulation of the Huddle’s core, driven by a network of impulses based on the player’s direction and the local environment, which allowed the Huddle to reconfigure as needed in certain situations, such as adaptation in confined spaces.

Finally, I found it very interesting that for the skin they created a mix of artistic styles borrowed from the sculptures of John Isaacs and the art of Jenny Saville and Rembrandt.

THE ABSENCE OF MUSIC THAT LEAVES THE PLACE TO AN EVEN MORE EFFECTIVE SOUND PRESENCE

Inspired by the horror B-movies of the 80s, Martin Stig Andersen in collaboration with SØS Gunver Ryberg, composed the soundtrack of Inside, making extensive use of synthesizers. Again in comparison with Limbo, here too, Anderson did not want to create a real soundtrack, but rather particular and evocative sounds, such as those reproduced using a human skull as an instrument from which sound could enter and exit, a sound that could lead back to that of the “bones”, creating this dark and cold atmosphere, very suitable for the context.

This time, Andersen worked closely with the developers, creating an integration between the visual element and the audio element, such as the movements of the protagonist’s chest during breathing, which correspond to sound effects in perfect synchrony.

Playdead began working on Inside shortly after Limbo’s release, using the same custom game engine, but switching to Unity to simplify development, and adding their own rendering routines, later released as open source. The game was partially funded by a grant from the Danish Film Institute .

It is now quite evident that this great Danish team has decided to create a strong recognizable style, not only in terms of the graphic aspect, but also for the game design. Here, too, we basically have a platform-puzzle, but with more complex systems, both in terms of the importance of the physical component and the “trial & error” system, which basically means learning from your mistakes. Even in Inside, the brutal deaths of the protagonist (here rendered even more graphic than in Limbo) are inevitably frequent, but at the same time the checkpoints are just as frequent. This aspect allows the player to try as many times as necessary to overcome and solve the various puzzles.

The puzzles are initially quite easy, serving as a short but comprehensive tutorial for the game mechanics, however, as you progress, they become more elaborate and complex, forcing the player to make good use of the lessons taught previously and learned dearly at a price (for the poor protagonist).

There is also the addition of a small exploratory component, especially useful for finding the spheres which, once collected, will allow you to unlock the alternative ending.

It’s a game that tests our ingenuity while reminding us of a fundamental theme: the mind can be more powerful than physicality or weapons at times in order to save oneself from enemies who are disproportionately stronger and larger than we are.

Are you, by any chance, referring to the nerds’ revenge?

Useful links: