A contemplative journey through the silence of solitude, the weight of memory, and the haunting beauty of decline.

In Rays of the Light is a first-person narrative adventure – a walking simulator developed by Russian indie creator Sergey Noskov, known for titles such as 7th Sector and the earlier The Light from 2012. This version, published by Sometimes You in 2020, is essentially a modern remake, featuring real-time 3D graphics and significant technical improvements, while remaining faithful to the original’s contemplative spirit.

The game is available on PC (Steam), PlayStation 4/5, Xbox One/Series S|X, and Nintendo Switch, with a short overall playtime estimated at 1-2 hours to complete both endings. It stands as a truly contemplative indie experience, offered at a very accessible price.

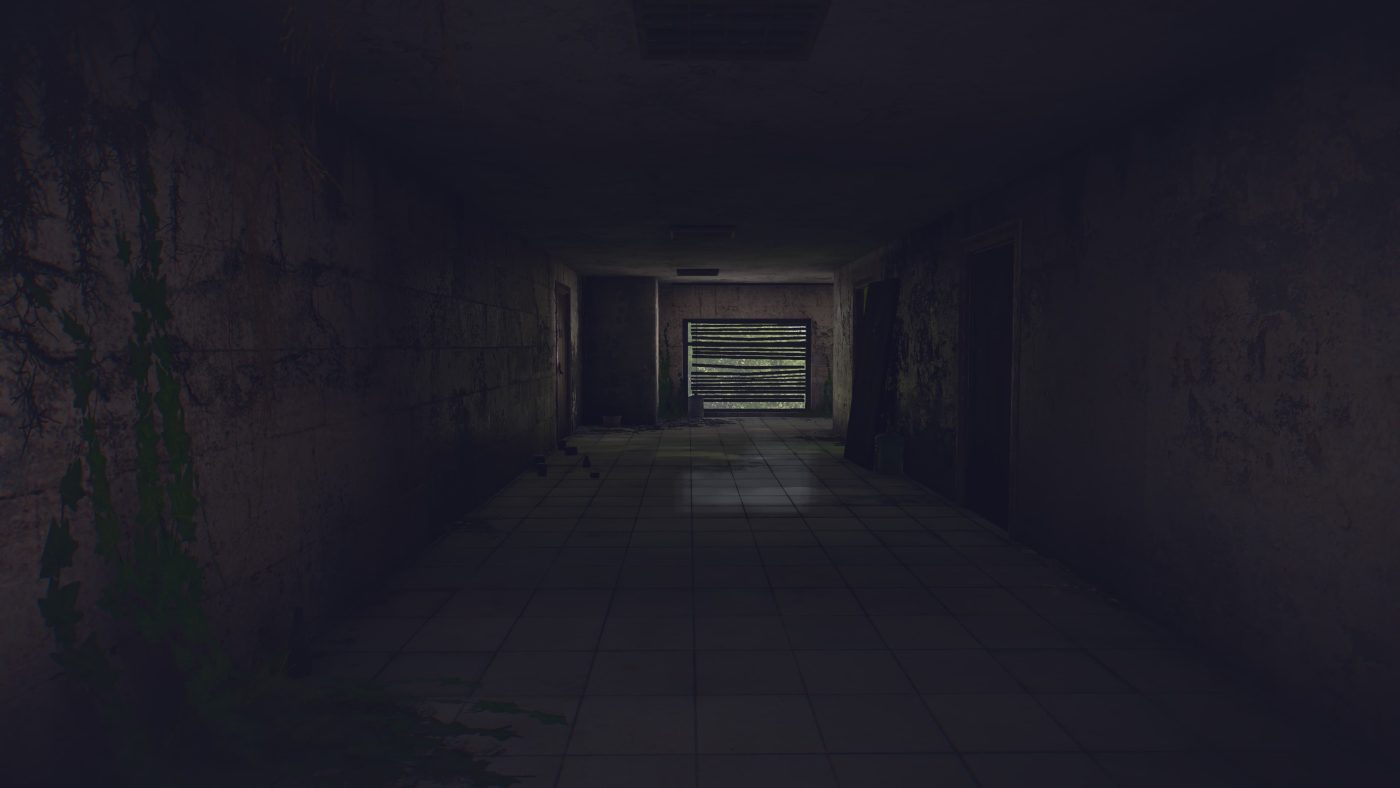

The narrative structure invites players to explore, in solitude, an abandoned school and an underground bunker, uncovering documents, notes scrawled on walls, and fragments of text that slowly reconstruct what happened to human civilization – without dialogue or active characters. It is a meditative, atmospheric experience, aimed at those who appreciate silence, empty spaces, and reflection on time and the consequences of our actions.

The game’s goal is not to entertain through action or complex mechanics, but to evoke emotion through decaying environments, emotive music, and ambient sounds—a silent lobby of nothingness, punctuated only by creaking footsteps or distant sirens. The few puzzles – such as locker codes, numerical combinations, and keys to find – are simple and intuitive, few in number, and serve to pace the exploration without becoming tedious.

In Rays of the Light delivers a short, yet artistically resonant experience, capable of leaving a lasting emotional impression through its evocative atmosphere, melancholic soundtrack, and understated, immersive storytelling. It’s a quiet, poignant departure from the chaos of mainstream action titles – an invitation to pause, reflect, and feel.

An Indie Voice from Russia

The main creative force behind In Rays of the Light is Sergey Noskov, an independent Russian developer known for his deeply personal and auteur-driven approach to game design. The title is a clear example of what is often referred to as “solo development” – Noskov handled virtually every aspect of the original production, from writing and programming to level design and artistic direction.

Originally conceived as a remake of his earlier 2012 game, The Light, this modern version is the result of both technical and conceptual reworking, reflecting the developer’s artistic growth and maturity.

Noskov had already garnered international recognition in the indie scene with 7th Sector (2019), another atmospheric experience praised for its enigmatic world-building and immersive soundscape. Across both titles, a distinctive poetic voice emerges: a world of desolate environments, profound silence, and narratives told through space rather than words. Noskov embraces minimalism – both in storytelling and interaction – and strongly believes in the power of the environment to communicate emotion and explore existential and philosophical themes. In Rays of the Light is a testament to that vision.

Sound design also plays a crucial role, and for this project, Noskov once again collaborated with composer Dmitry Nikolaev, his creative partner on 7th Sector. Their synergy is evident in the way music is used not as mere background, but as a narrative instrument in its own right.

Although not widely known outside the Russian indie scene, Nikolaev demonstrates a rare sensitivity in composing sonic landscapes capable of evoking complex emotions such as solitude, guilt, and abandonment.

The game was published by Sometimes You, a small independent publisher headquartered in Russia, dedicated to bringing indie titles to a broader audience through console platforms. Since its founding in 2014, the company has carved out a significant niche, acting as a bridge between small developers and major distribution channels such as PlayStation Store, Xbox Live, and Nintendo eShop.

While their catalog spans various genres, Sometimes You is best known for supporting experimental and artistically driven games like Blind Men, The Mooseman, and Energy Cycle. Despite modest budgets, the publisher ensures multi-platform releases and provides essential technical assistance to indie developers, even in markets that are typically more difficult to access – such as console environments.

Sometimes You has also gained attention for its efficiency in porting low-cost games across multiple platforms, making niche projects more widely accessible. However, the publisher has occasionally faced criticism from both media and players for releasing games that are technically unpolished or notably short – a reflection of its business model, which favors volume and creative experimentation over painstaking refinement.

A Narrative to Piece Together

The plot is deliberately cryptic, fragmented, and deeply symbolic. There is no explicit linear narrative, nor are there characters to interact with: everything is conveyed through the environment, the objects left behind, and the messages scattered across abandoned places. The player assumes the role of an anonymous individual who wakes up alone inside a school building, immersed in a deserted, ruined world. No initial context is provided: there are no dialogues or introductory texts. One is simply left to wander silently through empty corridors and rooms shrouded in the dust of time. As exploration progresses, it slowly becomes clear that the world has undergone a catastrophic event.

Set in a city of the former Soviet bloc, likely post-nuclear, the setting hints at a global collapse – perhaps caused by atomic energy, pollution, or sheer human neglect. Handwritten notes, blackboards covered in formulas, faded photographs, and broken radio devices begin to build a disturbing narrative framework. References emerge to the collapse of society, the sudden abandonment of buildings, and a vanished humanity.

The discovery of an underground bunker marks a turning point in the narrative. Here, the tone grows darker and more frightening, claustrophobic: cramped rooms, unsettling background noises, and increasingly cryptic messages trace the mental path of those who had taken refuge there, struggling with fear and guilt. The descent into the bunker serves as a metaphorical inward journey – a kind of purgatory for the soul – where the protagonist, and by extension the player, confronts themes of guilt, redemption, and oblivion.

The game culminates in one of two possible endings, hinging on a simple yet deeply symbolic mechanic: exposure to light. Should the player spend more time outside, basking in sunlight, they are rewarded with a positive, luminous, and serene conclusion. Conversely, if they remain predominantly indoors, shrouded in darkness, the game offers a bleaker, more despairing epilogue. This subtle moral choice is difficult to predict, allowing the player’s impulsive nature to surface – reflecting their willingness or reluctance to face reality, step into the light, or retreat into the shadows of the past.

Ultimately, the entire plot unfolds as a grand allegory on the end of humanity and the survival of the natural world. The protagonist is not a hero, but a witness – the last one – to what once was. Their story, much like that of the world itself, is not told through events, but through traces: forgotten objects, wall writings, and silences laden with meaning. It is a dense, environmental narrative demanding attention, sensitivity, and active engagement from the player.

Thought-Provoking and Existential Themes

In Rays of the Light is, above all, a contemplative video game, where every element – from gameplay and visual direction to music and environmental storytelling – is meticulously crafted to evoke philosophical and moral reflection. The game grapples with complex existential themes through a somber and meditative tone, yet it never lapses into rhetoric. It is a work that refrains from offering definitive answers, instead inviting players to confront fundamental questions about existence, memory, guilt, and the intricate relationship between humanity and the world it inhabits.

At its core lies the theme of solitude, understood not merely as a physical state but as a profound condition of the soul. The world presented is desolate and uninhabited, yet saturated with human traces: forgotten objects, faded photographs, cryptic writings, and stains on crumbling walls. No NPCs, no voices interrupt the silence – the only constant sound is the echo of one’s footsteps. This solitude becomes a powerful vessel for introspection, compelling the player to reckon with their presence in a space seemingly forsaken by humanity, as though time itself continued to flow long after everything else ceased.

Another pivotal theme is collective responsibility. Though the precise cause of the catastrophe remains unstated, environmental details – signs warning of nuclear energy, quarantine zones, abandoned scientific instruments – imply a disaster wrought by human folly. The game does not point fingers at a single event but constructs an implicit accusation against the arrogance and shortsightedness of modern humanity. It is the classic post-apocalyptic motif: what remains is not only a destroyed world but the moral consequences of misguided choices.

Interwoven throughout is the motif of nature reclaiming its dominion. Vegetation sprouts through cracks in walls, trees entwine with fractured asphalt, and natural light filters into spaces once sealed shut. This is far more than mere visual poetry – it is a testament to nature’s enduring resilience. Where humanity has failed, life persists, silent yet unyielding. Though tinged with melancholy, this vision offers a glimmer of hope: the world does not conclude with us but regenerates anew. It is an ecological perspective conveyed with quiet observation rather than dogma.

Finally, there is the theme of light as a metaphor for moral judgment. The entire game is built around a dialectic between light and darkness – not only visually but symbolically. Light represents truth, acceptance, perhaps even redemption, whereas darkness stands for denial, fear, and isolation. This is hinted to the player from the very beginning, manifesting in the gameplay itself: the time spent in light or shadow determines which ending is reached. It is a subtle yet powerful message: choosing the light means facing reality and striving to live with it, while choosing darkness is a retreat into guilt and denial.

In Rays of the Light thus emerges as a poignant meditation on the human condition, our entwined existence with the world, and the inner landscapes we inhabit. It is a reflection on time, the consequences of our deeds, and the enduring sanctity of memory. An experience that, despite its apparent simplicity, leaves room for a complex and profound existential interpretation.

Evocative and Well-Executed Art Direction

The visual impact of In Rays of the Light stands as one of its most distinctive and compelling features. The game heavily employs environmental storytelling through the composition of spaces, texture choices, and the way light interacts with the environment. Despite being a low-budget production, the art direction manages to convey a profound sense of abandonment, melancholy, and decaying beauty. The graphics engine used is Unity, a common choice in the indie scene, which Noskov skillfully leveraged for his expressive purposes. Compared to the original 2012 version (The Light), this remake leverages an updated engine to introduce volumetric lighting, dynamic shadows, real-time reflections, and, most critically, a global illumination system that plays a pivotal role in shaping the atmospheric depth of the game world.

The environments, while largely static, are rich with detail: every object – be it a crumpled piece of paper, an overturned chair, or a chalk-streaked blackboard – carries narrative weight. Nothing is left to chance. The visual style draws heavily on post-industrial Soviet aesthetics: peeling walls, Russian signage, functionalist architecture, bunkers, classrooms furnished with vintage fixtures, and outdated equipment. This creates a palpable sense of realism – not merely in graphic detail but in the cohesive integrity of the whole. Rather than relying on cutscenes, the environment conveys its story through an accumulation of visual clues. Player interaction remains minimal, yet the level design is meticulously crafted to encourage close observation and interpretive engagement.

Light emerges as the undisputed protagonist of the scene: the way it streams through a broken window, reflects on the wet floor, or illuminates a key object sets the rhythm and direction of exploration. There are moments when the light seems to guide the player, creating a sharp contrast between open environments and closed spaces, between the nature-reclaimed outdoors and the claustrophobic, decaying interiors. The darker zones, such as the underground bunker, employ deep shadows and cold color palettes to evoke a sense of oppression.

From a technical standpoint, although some textures lack detail and environmental assets can sometimes feel repetitive, the artistic value of the whole is not compromised: In Rays of the Light does not aim for photorealism – though it occasionally touches it – but rather to emotional resonance and evocative storytelling. Special mention must be made of the chromatic minimalism. The color palette ranges through neutral tones, beiges, grays, greenish hues, and touches of rust. This limited use of color amplifies the effect of sunlight, which appears almost as a spiritual element in an otherwise muted world. When reaching more open spaces or stepping outside, the sudden presence of green creates a striking and evocative contrast.

In sum, the art direction of In Rays of the Light masterfully crafts a quiet yet profoundly narrative world, employing visual design as a compelling storytelling instrument. Despite some technical constraints, the work attains a harmonious and poetic aesthetic that impeccably fulfills its vision: a raw, melancholic beauty that eloquently evokes memory, time, and silence.

The Language of Sound

In a work like In Rays of the Light, where action is sparse and silence becomes a language itself, the sound design assumes a pivotal role. Far from being a mere atmospheric layer, the soundscape is a fundamental narrative device, capable of evoking emotions, tension, and solitude more powerfully than words ever could. Noskov’s world does not speak through voices but through echoes, sonic voids, and the haunting absence of human noise – save for the subtle sounds of footsteps and heartbeat.

The soundtrack, composed by Dmitry Nikolaev – renowned for his work on 7th Sector – perfectly complements the game’s contemplative and intimate mood. Centered predominantly around soft piano compositions, often sparse and slow-paced with isolated notes that seem to fade into the void, these melodies are intertwined with layered ambient sounds: electrical hums, the whisper of wind, dripping water, creaking old furniture, and crumbling structures. Each environment is endowed with a distinctive and coherent sonic identity. Natural sounds play an equally vital role: distant bird calls, rustling leaves, and the crunch of grass underfoot infuse life into an otherwise seemingly desolate world. This juxtaposition – between the absence of humanity and the resilience of nature – is amplified through the game’s meticulous audio design. Silence often becomes a form of language itself, laden with meaning; it weighs heavily, unsettling rather than comforting. It is precisely in these moments of profound silence that small, normally overlooked sounds gain narrative significance.

The transition from the open outdoors to the oppressive underground bunker is especially masterful. Descending into the bunker, music becomes sparse, nearly absent, supplanted by dissonant sounds: metallic drones, intermittent electronic pulses, eerie echoes, and ghostly reverberations. At times, the environment seems to communicate nonverbally, sending cryptic signals. Vocal elements are scarce and limited to brief, distorted, and barely intelligible phrases, functioning more as textural components than dialogue. From a technical standpoint, the sound design performs impressively. Ambient sounds are three-dimensional, responding coherently to the player’s movements and surroundings. Walking on different surfaces – grass, metal, or concrete – produces realistic auditory feedback. The intelligent use of reverb helps emphasize spatiality, especially in underground corridors and enclosed spaces.

Considering the inherent constraints of an indie production, the sound design of In Rays of the Light is remarkably refined. Dmitry Nikolaev crafts a restrained, melancholic soundtrack that consciously eschews sentimentality, embracing instead a near-spiritual sensibility. When skillfully balanced, silence resonates more profoundly than any melody – it is precisely this delicate interplay between sound and silence that endows the game with its deepest and most resonant identity.

Simple yet Effective Gameplay

As a profoundly narrative experience, the gameplay is stripped down to its bare essentials, allowing space for reflection and contemplation. At first glance, the game may seem to offer little in the traditional sense: no combat, no structured missions, and no conventional inventory system. Yet, it is precisely this minimalism that defines the work’s unique value, situating it at the crossroads between a video game, an art installation, and an interactive poem.

Players are granted the freedom to explore an apparently abandoned environment: beginning in a decaying school building, extending to a courtyard, an overgrown outdoor area, and finally, a subterranean bunker. The entire experience unfolds in first-person perspective, with controls limited to walking, interacting with select objects, and gathering subtle narrative clues – notes, written messages, symbols, photographs. Navigation is guided by environmental landmarks and carefully crafted visual cues, often illuminated by light.

The pacing is deliberately slow, almost meditative. There are no timers, enemies, or punitive mechanics for errors. This design choice serves a clear purpose: to encourage active and attentive observation. Even the smallest details – graffiti on a wall, the placement of a chair, sunlight streaming through a window – carry narrative weight. Puzzles are sparse and mainly serve to modulate the rhythm: finding a key to unlock a door, decoding a numeric combination, or pulling a lever to reveal a hidden passage. These challenges remain accessible and are seamlessly integrated into the world.

In terms of world-building, the game masterfully conveys a rich narrative without relying on cutscenes or dialogue. The environmental coherence is meticulous: every object serves a purpose, and every space evokes a distinct mood. The opening school setting, for instance, immediately conveys a sense of abandonment alongside a life abruptly halted – disordered desks, a broken bottle, and a silent telephone.

Outside, nature has reclaimed the space: trees sprout through cracks in the asphalt, moss blankets the walls, and unseen animals seem to silently inhabit the empty surroundings.

The second half of the game, set in the bunker, takes on a drastically different tone. Here, the world-building takes on a more unsettling and claustrophobic dimension, featuring flickering neon lights, distorted noises, and bare walls that seem to weep anguish. It is a world that suggests madness, fear, and the loss of humanity. The environment becomes a psychological mirror reflecting the protagonist – and, by extension, the player – where progress is not merely physical but deeply symbolic.

One particularly compelling feature is the integration of the theme of light into the gameplay itself. As previously noted, the game monitors the amount of time the player spends in sunlight versus darkness. This choice influences the ending, transforming light from a mere visual element into an implicit moral mechanic. Without relying on explicit stats or dialogue choices, the game crafts a subtle yet coherent system of decision-making that aligns seamlessly with its overarching vision.

Though minimalist, the gameplay is deeply meaningful and thoughtfully crafted, condensed into a brief experience of under two hours. Players craving fast-paced action may find it lacking, but those open to a slower, more reflective pace will uncover a world built with meticulous coherence, elegance, and rich symbolic depth. Eschewing traditional challenges, the game invites you to slow down, observe, and truly listen.

Not Everyone’s Cup of Tea

In Rays of the Light has elicited sharply divided responses from critics and players alike, precisely because it defies conventional video game norms. On one side, it is celebrated as an interactive work of art, offering a deeply emotional and contemplative experience. On the other, it has drawn criticism for its slow pacing, sparse interaction, and limited adherence to traditional gameplay mechanics.

A key strength frequently praised is its artistic and narrative coherence. The game’s ability to convey a rich, complex story without the use of dialogue or explicit text stands as a masterful example of environmental storytelling. The interplay of visual ambiance, soundscapes, and thoughtful world-building crafts an immersive and evocative atmosphere, where every detail amplifies the game’s existential and philosophical themes. The soundtrack and sound design, in particular, have been singled out for their crucial role in evoking feelings of melancholy and isolation.

Nonetheless, many reviewers note that the experience can feel alienating to those expecting a more dynamic or structured gameplay. The absence of meaningful challenges, clear objectives, or traditional progression may render the game monotonous or overly slow for some, while the lack of explicit guidance can complicate navigation and interpretation. Additionally, the minimalist interface – though functional – may be unintuitive for players unfamiliar with experimental games.

On the public reception front, the game has steadily cultivated a small yet devoted following – enthusiasts of artistic and indie experiences who value its emotional depth and poetic visual storytelling. For these players, In Rays of the Light exemplifies how video games can transcend mere entertainment to become a form of artistic expression, conveying profound and meaningful messages.

Thus, critics recognize In Rays of the Light for its distinctive identity and cultural value, while also noting its limitations regarding accessibility and gameplay variety. It is a title that demands patience, sensitivity, and a reflective mindset – qualities that may not appeal to all, yet it possesses the power to leave a lasting impact on those who truly embrace its essence.

In Rays of the Light

PRO

- Deep and immersive environmental storytelling: the game weaves a rich, emotionally resonant narrative without relying on dialogue or cutscenes, instead using space, light, and silence to powerful effect.

- A uniquely evocative atmosphere, crafted through a masterful blend of art direction, sound design, and lighting.

- Outstanding sound design and minimalist soundtrack: subtle audio cues and ambient compositions evoke a profound sense of solitude and melancholy, amplifying the emotional depth.

- Remarkable artistic and thematic coherence, where every visual and sonic element contributes meaningfully to the game’s existential and philosophical undertones.

- Convincing and layered world-building: environments, though minimalist in form, are rich in narrative cues and invite personal reflection.

- Innovative use of natural light: the passage of time and sunlight subtly influence the ending, introducing an implicit moral dimension.

- A quiet, meditative experience, ideal for players seeking an indie title that transcends conventional entertainment to offer something more introspective and thought-provoking.

CON

- Extremely slow pacing, which may not appeal to everyone – especially those accustomed to more engaging or action-oriented gameplay.

- Minimalist gameplay lacking traditional challenges: the limited interactivity and absence of clear goals may prove frustrating for players who prefer structured or fast-paced experiences.

- Lack of clear direction, which can lead to moments of disorientation or difficulty in fully grasping key narrative elements.