Game Director Sebastian Drews on how Constance harnesses brush and canvas as vessels for emotional healing, turning the invisible, lacerating wounds of trauma into a vibrant, living work of art — a transformative journey of catharsis, renewal, and self-discovery through the power of paint.

It’s been quite some time now—and we don’t mean just a few days, but weeks, even months—that Constance has quietly lingered on our radar. Ever since our eyes first settled on the third project from btf Games Department, the independent label operating under the German production company Bildundtonfabrik, we knew there was something uniquely compelling about it.

You might now be wondering: Why now? Why choose this moment for a deep dive?

The honest answer is—we don’t entirely know. There was no calculated timing, no editorial calendar dictating our move. Just an instinct, a shared certainty that this was the moment. Because Constance is not just a game. It’s a layered, introspective work of art—one that withholds as much as it reveals. A creation marked by emotional depth, stylistic nuance, and conceptual richness that simply couldn’t be captured through a cursory glance or a passing mention. It deserved more. It demanded more.

And so began our conversation with Game Director Sebastian Drews—a simple, sincere exchange in which we shared our intent: to dig deeper, to explore the creative and narrative foundations of Constance. Sebastian embraced the idea immediately, with warmth and enthusiasm. And, almost serendipitously, our proposal arrived just as the studio announced the game’s release date.

We took it as a sign. What better time than this? What better opportunity to invite you on a journey behind the curtain—into the heart of Constance, and the minds that brought it to life?

For us, there could be no better time. And that’s exactly what brings us here.

Before we begin, we’d like to extend our heartfelt thanks to Sebastian. A professional in every sense of the word—thoughtful, open, and profoundly passionate about his craft. His love for this medium, and for the boundless creative potential it offers, is evident in every word he shared with us. To speak with him, even from afar, and to bring his vision to you, has been nothing short of a privilege.

A magical one, even—much like the extraordinary inner world we’re about to step into.

So, without further ado, make yourself comfortable and join us on this exclusive deep dive into the world of Constance.

The Interview

Hello Sebastian, and welcome aboard the expansive vessel that is Indie Games Devel — it’s truly a pleasure to have you with us for this special deep dive into Constance. Thank you for accepting our invitation. Before we delve into today’s central theme, we’d like to rewind the tape even further — back to the early days of your journey, when you began shifting from a passionate player to a true creative voice, from a consumer to a fully-fledged author. Could you tell us more about yourself, your artistic and creative path, and how that journey eventually led you to Constance? More broadly, who is Sebastian Drews — both the person and the creator?

Sebastian: Hello, thank you so much for having me. It’s a true honor to be able to answer such in-depth questions about my creative journey and our game Constance. So yes, I am Sebastian, 32 years old from Cologne, Germany. My journey as a video game consumer started quite early in life. I remember playing video games at around three years old, starting with educational games—preschool-type games with Mickey Mouse. I remember some exercises with numbers and letters, and it was a special feeling playing those. I really enjoyed them.

We were lucky because my uncle worked at IBM, so we had early access to a DOS and then Windows 95 computer at home, which not many people had at that time. I was able to play Commander Keen and Rayman when I was about six years old, and that definitely shaped my taste for platformers.

That was the beginning of my gaming life. In terms of my professional journey, I started out as a more visual person. I was really interested in movies—shooting film, using cameras, and video editing. That was my passion for a long time. When I was ten, I had a LEGO set called LEGO Studios, which made a big impact on me. It included a webcam, and I connected it to what was probably a Windows 98 computer. It came with a very simple editing software, and I started shooting stop-motion short films with my LEGO sets. That was my creative outlet for quite a while. Over time, the cameras got better, the software more complex and expensive, and I started shooting music videos for friends and some clients.

I studied media informatics, always leaning toward the media side of things. After graduating, I found a job as a graphic designer for a TV production company in Germany, working on game shows and other productions. That was a great entry point for my career. Video games were always a hobby, but I consistently dabbled in game development too. I tested out all kinds of software—GameMaker, Unity, Unreal—but I always had ideas that were way too big.

During university, I made the classic mistake that many beginner game developers make: overscoping. A small group of friends and I decided to make a game, and our first idea was, of course, a multiplayer online battle arena. We had absolutely no chance of building that. None of us had any experience. We worked on it for maybe two months, then realized it wasn’t going to happen. Instead of scoping down, we just gave up.

In my free time, I kept trying to make games solo. I had an idea for a mobile game and started to scope it more realistically. But I built it completely the wrong way. My programming knowledge from university was basic, so I tried to use Unity’s UI system—which is complex and limited—to build the whole game. I quickly hit the limits of what was possible and scrapped that idea too. That cycle continued for a while.

Eventually, I became very unhappy with my job. I switched companies and became a motion designer—shifting from graphic design to animation, which was a great fit because I’d always loved stop-motion and video editing. I started working at my current company, Bildundtonfabrik (btf), where we’re now making Constance. btf created the Netflix series How to Sell Drugs Online (Fast) and other productions like TV shows and documentaries. I actually watched season one of that series on my own and thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to work on something like this?” Then I realized they were based in my city. I applied three times. The third time worked out, and I got hired for season two.

That was exciting for a while, but after two and a half years, I started to feel the same creative frustration I’d felt in previous jobs. I needed a change. That’s when I picked up Unity again—but this time more seriously. I followed YouTube tutorials to build a solid foundation and started prototyping Constance on my own.

Constance was different from all my earlier game ideas. Those were fun, random concepts without much emotional depth. Constance felt necessary—it was something I had to do. It became my escape from a career path that I realized wasn’t right for me. Working on Constance felt like the right thing to do.

I developed the prototype over about nine months while still working full-time. Nights, weekends—any spare time I had went into Constance. It was not good for my mental health. I was struggling—depression, anxiety, panic attacks on my way to work. But the process of building Constance gave that pain purpose. It shaped the story of the game. Constance is a representation of my personal journey.

After nine months, I pitched it to my boss. We were actually supposed to be discussing a different series, but at the end of the meeting, I briefly introduced Constance. He said he wanted to do more games and connected me with the game department. We’re fortunate in Germany to have a games funding program. Together with our producer Robert, we put together a pitch paper and applied for funding. We got it, destiny connected me with Leo, the best programmer (and amazing friend) I could have ever found for this project, and we began the search for the rest of the team to start working on the real version of Constance.

Everything I had done up until that point was just pre-alpha—just proof of concept. With the team and funding, we could finally begin working on the true Constance.

At btf Games, you describe yourselves as “a community of dreamers, creators, and innovators.” This concise yet impactful slogan perfectly encapsulates your brand identity — a close-knit team of about 20 passionate individuals bound by a deep love for the video game medium and the broader creative arts. Could you elaborate on the underlying philosophy that shapes your creative vision? What core mission drives your studio, what messages do you seek to convey through your craft, and how do you, within your creative ethos, perceive the value of video games—not merely as entertainment, but as an essential artistic and cultural medium?

Sebastian: You basically already touched on the most important point in your question—that for us, games are not just passive entertainment. They’re essential as an artistic and cultural medium. It’s incredibly important to us that our projects, our games, are adventures that actively do something with the audience.

We want players to go on fantastic, creative journeys and experience emotions they wouldn’t get from a book or a movie. We believe we’re creating meaningful adventures—not just throwaway stories, but experiences that stay with you, that can change or help you, offer new perspectives, or inspire you.

That’s the driving force behind everything we do.

Trüberbrook (2019), The Berlin Apartment, and Constance — three distinct works, each with its own voice and identity, yet all seemingly bound by a common thread: a deeply rooted artistic vision that places art not merely as an aesthetic layer, but as a narrative language and a philosophical core. This artistic sensibility appears to be the heartbeat of your creative output, even as each project carves out its own stylistic and conceptual path. Before we delve into this new creative chapter, we’d like to take a step back and pose a broader question to you — as someone who has been instrumental in guiding the evolution of btf Games’ artistic identity. In your view, what is the common thread that weaves these three projects together? And conversely, what sets Constance apart from Trüberbrook and The Berlin Apartment, both in tone and in artistic execution?

Sebastian: This one’s not so easy. I wouldn’t really see myself as someone who’s guiding the evolution of our artistic identity. I think of myself more as a new, parallel path in what we’re doing visually with our games.

The common thread that ties all of our projects together—no matter how different they may seem—is that they all originated from a specific, personal experience. Each director or vision-holder behind these games had something real happen in their life that inspired the idea. That’s what gives the work its authenticity.

For me and Constance, as I mentioned earlier, it came from being stuck on my creative path, falling into a bad place mentally, and needing to find a way out. Creating Constance—both the story and the act of making it—became that path for me.

I know it was similar for Hans and Flo, the creators behind The Berlin Apartment and Trüberbrook. They each had life experiences that sparked the question: “What if this was a game?” And that led to their own very personal projects.

What sets Constance apart from Trüberbrook and The Berlin Apartment, aside from the obvious differences in genre and art style, is how the story is told. Constance is still narratively driven, but it’s a metroidvania action-platformer—so gameplay has a much stronger focus, and the storytelling unfolds in a different way.

In The Berlin Apartment, you play as the people who lived there across different time periods. You pretty quickly understand what’s going on, and the narrative is about uncovering the emotional and historical connections between those lives. Constance, on the other hand, drops you into a mysterious world without much explanation. It’s about slowly figuring out what’s happening as you play. The deeper you go, the more you begin to understand the world and your place in it. And by the time the credits roll, I think if you were to go back to the beginning and replay it, you’d see everything in a completely different light—which is something we really love about this genre.

It’s often said that to truly understand a creative work, one must look behind the curtain — to uncover the ideas and impulses that first brought it to life. And that’s precisely where we’d like to begin: at the very origin. As the Director of Constance, could you take us back to that initial spark — the thought, image, sketch, or concept from which your pen first began to move and that ultimately guided the creative journey? In your eyes, what would you consider the true genesis of Constance — the moment it all began to take shape?

Sebastian: Wow, this one’s even harder than the last question. A defining moment… well, it’s definitely not just one. But I do remember a few that, together, really marked the beginning of Constance—kind of the origin sparks for the whole project.

One of the biggest was finishing Hollow Knight. Like for so many people, that game was something really special. But for me personally, it did something very specific: it threw me back to my roots, to the games I played as a kid like Rayman and Commander Keen. Of course, I’ve played a lot of platformers over the years, but this was different. It reconnected me with the genre in a really deep way and reminded me of why I loved it so much in the first place. That experience gave me this spark of, “Yes—this is the kind of game I need to make. This is the genre I should explore.” Not because of what anyone else thought, but because it felt true to me.

Another moment that stands out happened on the set of How to Sell Drugs Online Fast. I was working on the show with my friend Jussi, and during a break between scenes, we were outside talking. I told him—he was one of the first people I ever mentioned it to—that I wanted to make a video game. I shared this early idea I had: what if it was a platformer, something like a metroidvania in structure, but the character is a creative person fighting with Photoshop tools?

That was actually the original concept. It wasn’t just the brush—it also included things like the paint bucket, the selection tool, and others. These were the tools we used every day as creatives, as graphic designers, so it felt natural to turn them into mechanics. And the thought that no one had really made a game like that—that was motivating too. It felt fresh, like a new idea.

I also remember a moment with my girlfriend. I was standing in her kitchen, and I told her, “I think I want to make a video game.” And to this day, when we talk about that moment, she always says she didn’t know how seriously to take it. For her, it sounded like someone saying, “I think I want to learn piano”—just a hobby idea. But I think I was already serious about it in that moment. Because pretty much right after I told her—and after that conversation with Jussi—I sat down over the weekend, opened Unity again, found some tutorials, and just started working. So, yeah. Those are probably the few moments that really sparked the beginning of Constance.

Let’s delve even deeper — into the very heart of Constance’s inner world — to uncover the original vision that, as the project’s Director, led you to breathe life, movement, color, and nuance into every facet of the game. From the environments and everyday objects to the characters and even the enemies — those dark forces that stand between Constance and her search for truth within a fragmented, decaying reality — each element feels meticulously shaped by a cohesive artistic vision, with painting emerging not simply as a visual motif, but as one of the game’s central thematic pillars. In Constance, painting is no longer merely a form of artistic expression; it becomes something far more essential — a lifeblood, a driving force, the very leitmotif upon which the entire experience is built. How would you define the true role and meaning of painting within Constance? And what creative vision guided you throughout the development process — from the earliest conceptual sketches to the fully realized world we see today?

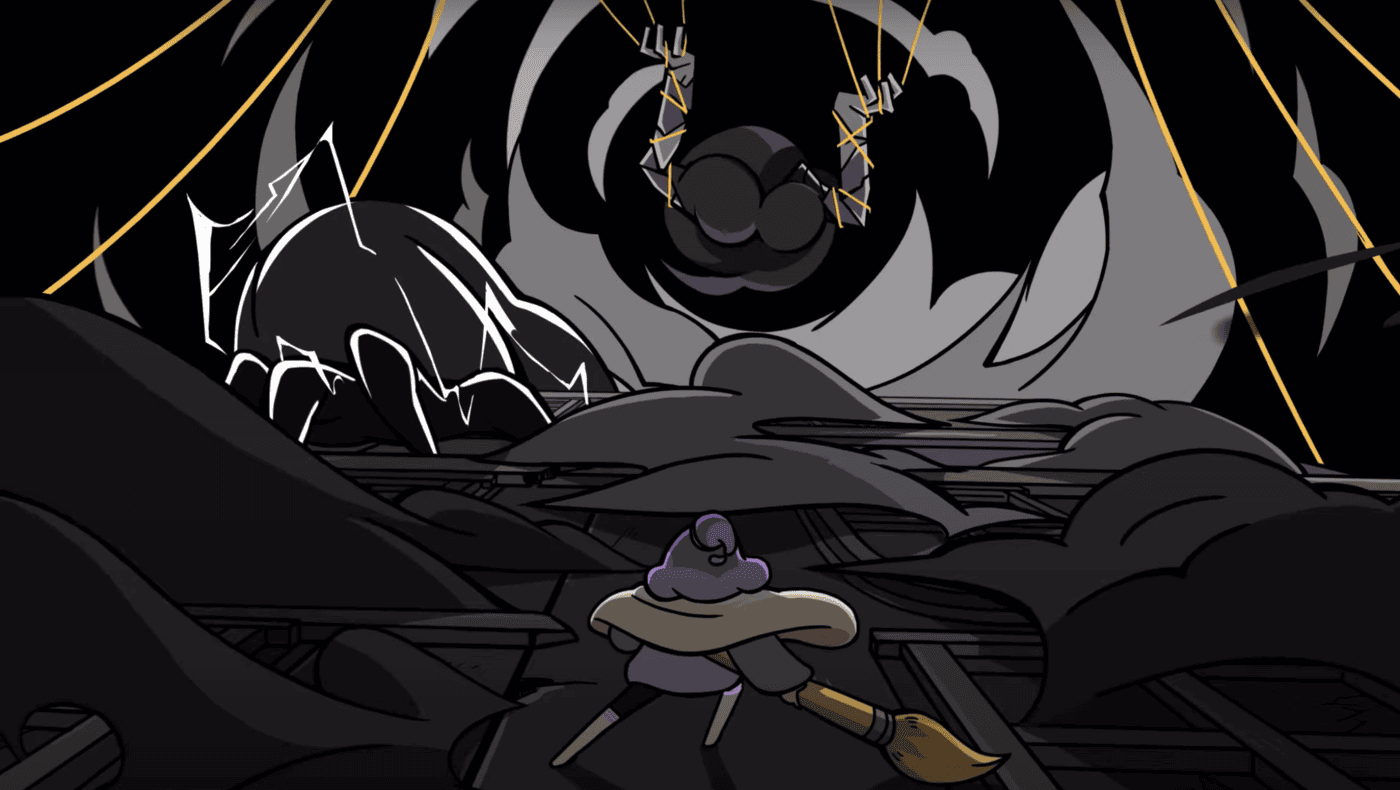

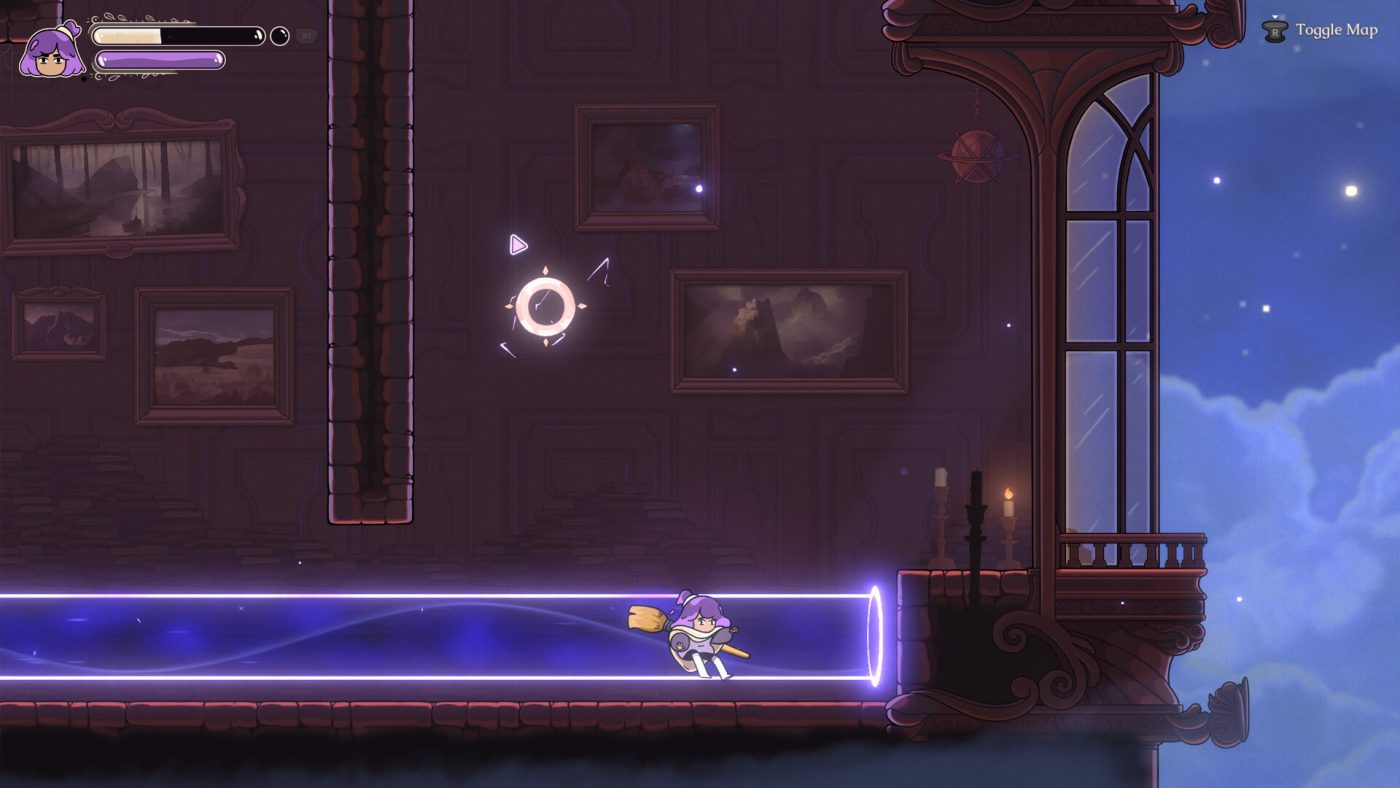

Sebastian: Yes, absolutely—painting and paint in general, along with the brush, are the essential driving forces behind Constance, both in terms of gameplay mechanics and narrative.

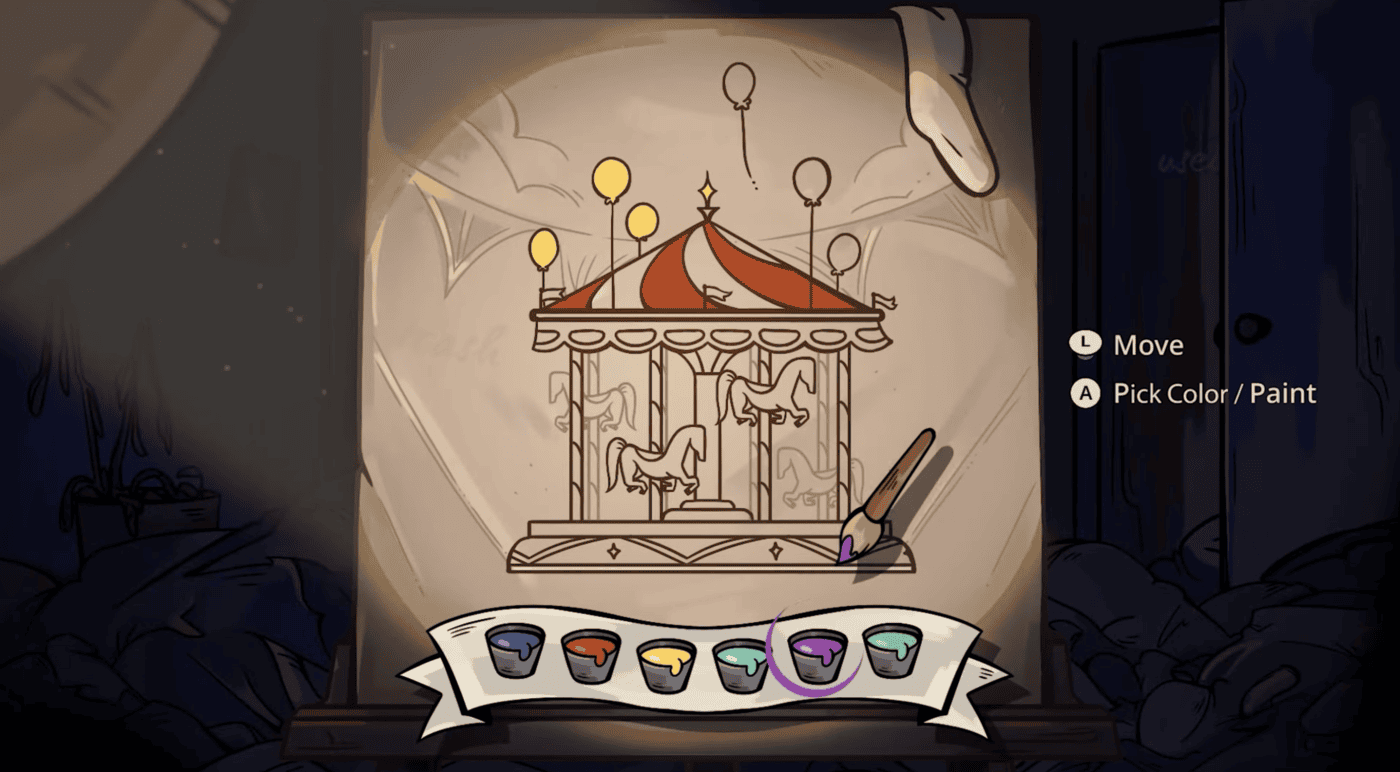

Gaining the brush in the game is a pivotal moment. It’s what gives Constance the ability to fight and survive. Without it, she wouldn’t be able to persevere or move forward in this world. Over the course of the game, the player unlocks more and more techniques for the brush, and through that, Constance becomes stronger and more experienced. You could even say she evolves from a beginner artist to a master by the end.

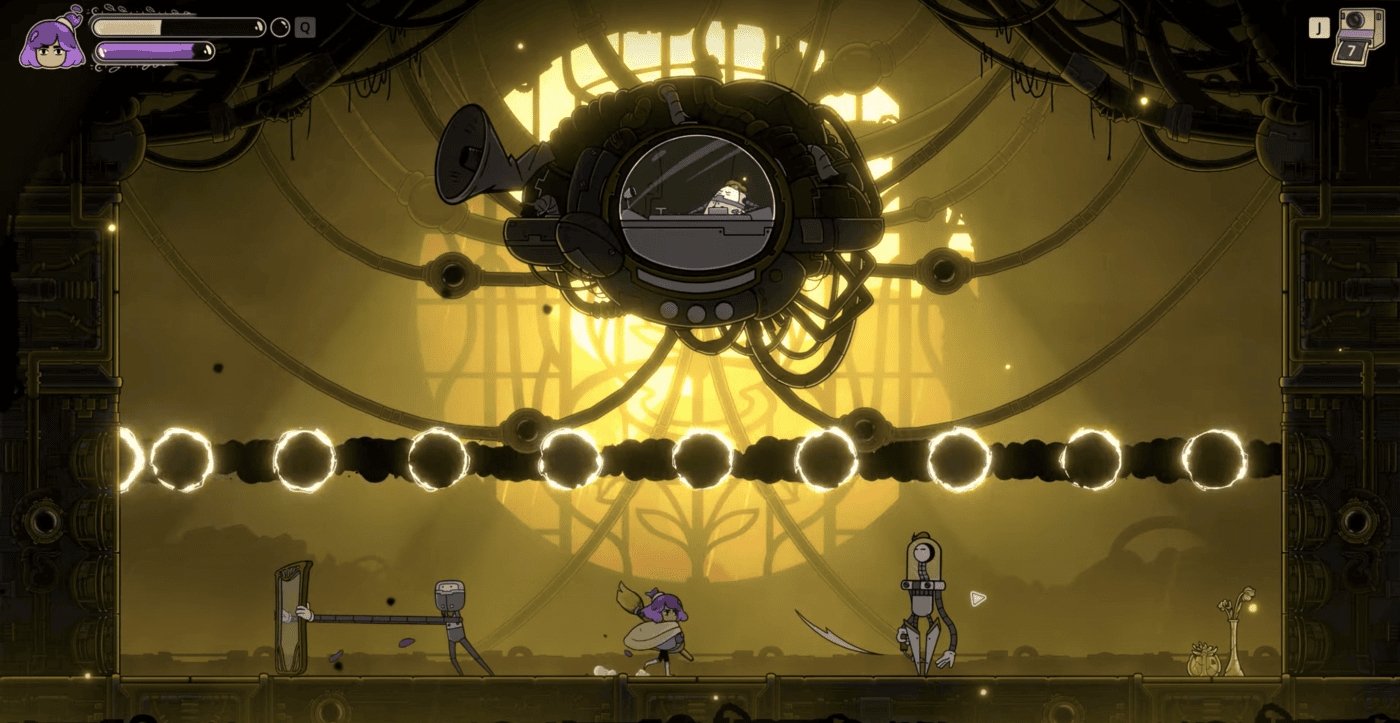

With these brush techniques, she’s essentially fighting for awareness and acceptance—especially self-acceptance. The act of painting, of creating, gives her the power to push through and uncover the roots of her mental health struggles, which is central to the story.

We’ve also built metaphor into the core mechanics. Like most games, there’s a mana system, but in our case, it’s a paint meter. And the paint doesn’t “run out” in a traditional sense—it becomes corrupted if misused. It’s all about balance and choices. You can’t just spam your abilities endlessly. If you overuse them, the paint corrupts, and eventually, that corruption begins to damage your health.

So the mechanic becomes symbolic: don’t overdo it, don’t burn yourself out, and understand that taking breaks is important. Different players will engage with the mechanics in different ways, just as people live their lives differently. What works for one person might not work for another, and that’s okay.

For us, that’s the crucial link between creativity and mental health—using painting not just as a gameplay feature, but as a metaphor for emotional resilience, personal expression, and self-discovery.

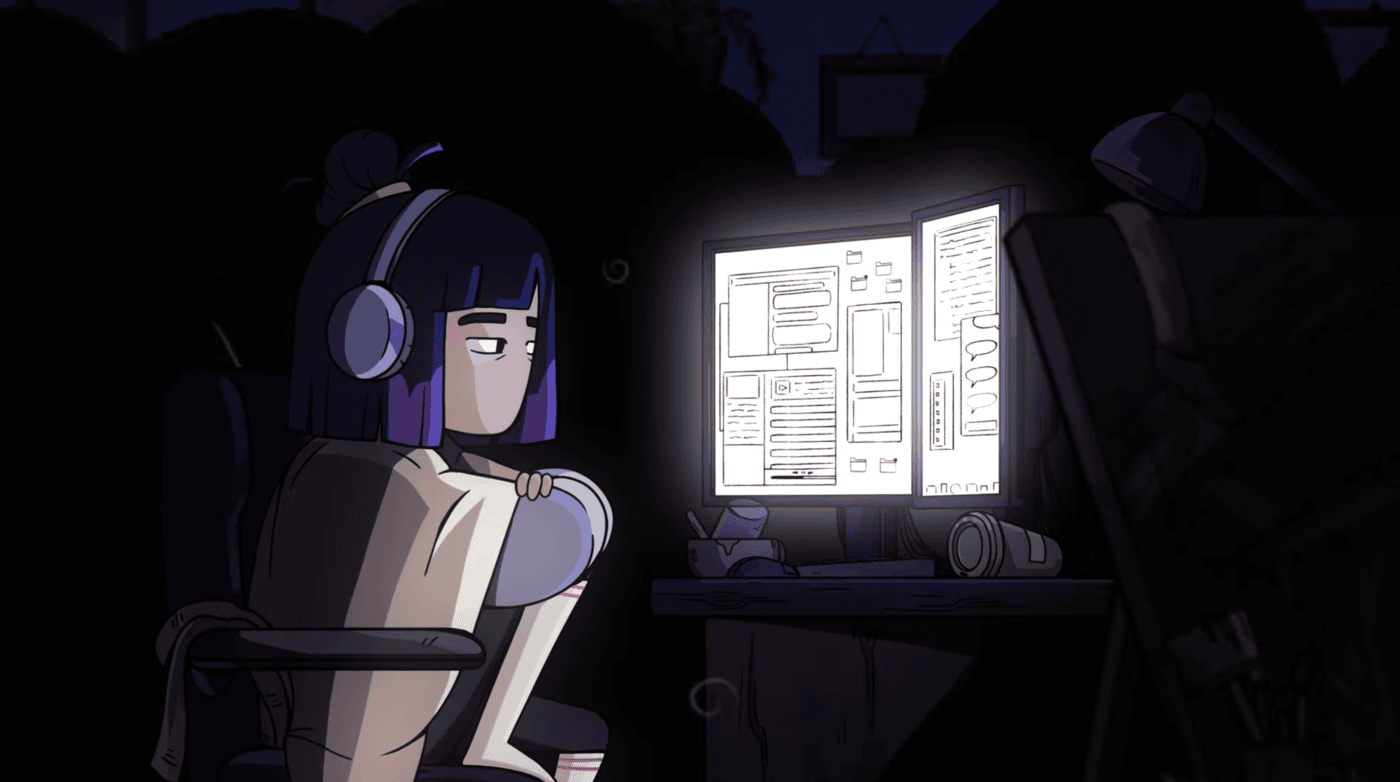

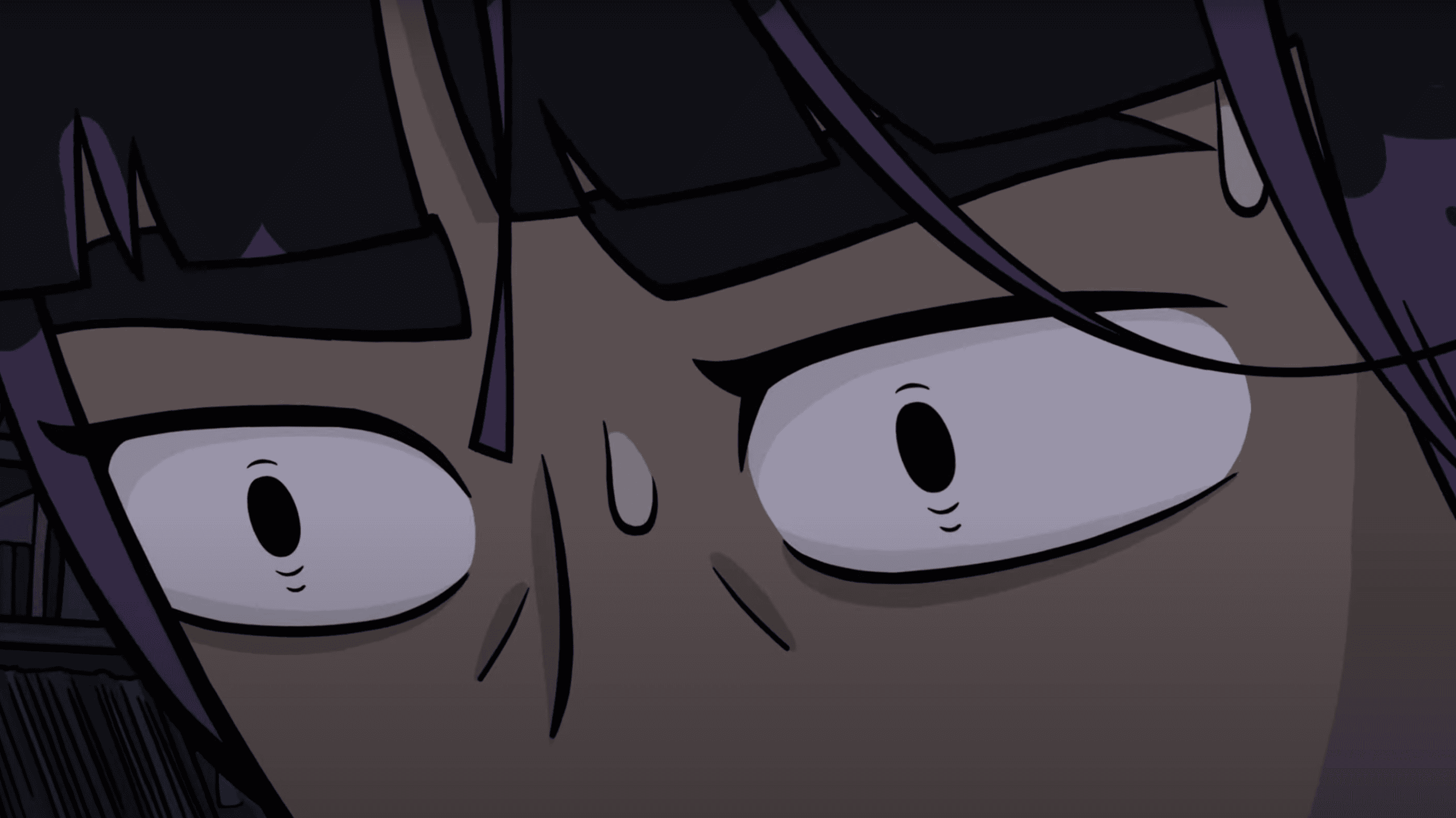

There’s no denying it — one of Constance’s most conceptually compelling features, even before considering its artistic direction, is its protagonist: the enigmatic, cryptic paintbrush-wielding artist at the heart of the narrative. She captivates not only through her distinctive style — from her attire to her unconventional hairstyle — but even more profoundly through the unique tool she carries. This is no weapon of destruction; rather, it is a brush — a creative instrument that does not erase or kill, but instead breathes life into the world, shaping it with color, form, and soul. What inspired the creation of such a unique protagonist? And how did the choice to center the game around a paintbrush-wielding artist influence both her character design and the overarching creative vision of Constance?

Sebastian: Like I mentioned earlier, the brush as one of the Photoshop tools was always there from the beginning. But when our game designer Edgar joined the project, we decided to simplify and focus solely on the brush for clarity, simplicity, communication, and identity. You don’t need to be a Photoshop artist or a creative person to understand what a brush can do. The other tools looked more cryptic and complicated, so we narrowed it down to just the brush.

The first designs of Constance looked very different — much more Rayman-inspired, and she didn’t really have limbs. But those early designs lacked a clear concept or grounding.

When Edgar joined, he looked at the mechanics and helped us figure out how the character design should align with the gameplay and story. We did a lot of shape design work and realized we wanted to keep the game’s tone wholesome and bubbly, almost cute, despite the heavy themes. We wanted that contrast, similar to the Ghibli style — sweet and appealing visuals paired with deeper, emotional topics underneath.

That need, combined with how important paint became for the mechanics, led to the final character design of Constance. Since it’s an inner world, inside her head, we weren’t limited by realism. So we went with the idea that her hair is literally paint.

While we understand that much of the narrative remains under wraps—save for a few tantalizing hints—could you share some insight or fragments that might help us begin to fathom the epic journey that awaits within Constance’s inner world? Does the game’s emotionally charged and psychological story arc follow the familiar framework of a traditional narrative-driven experience, or does it instead unfold with greater subtlety, through environmental storytelling and scattered glimpses into the past that invite players to piece together Constance’s psyche through fragmented memories?

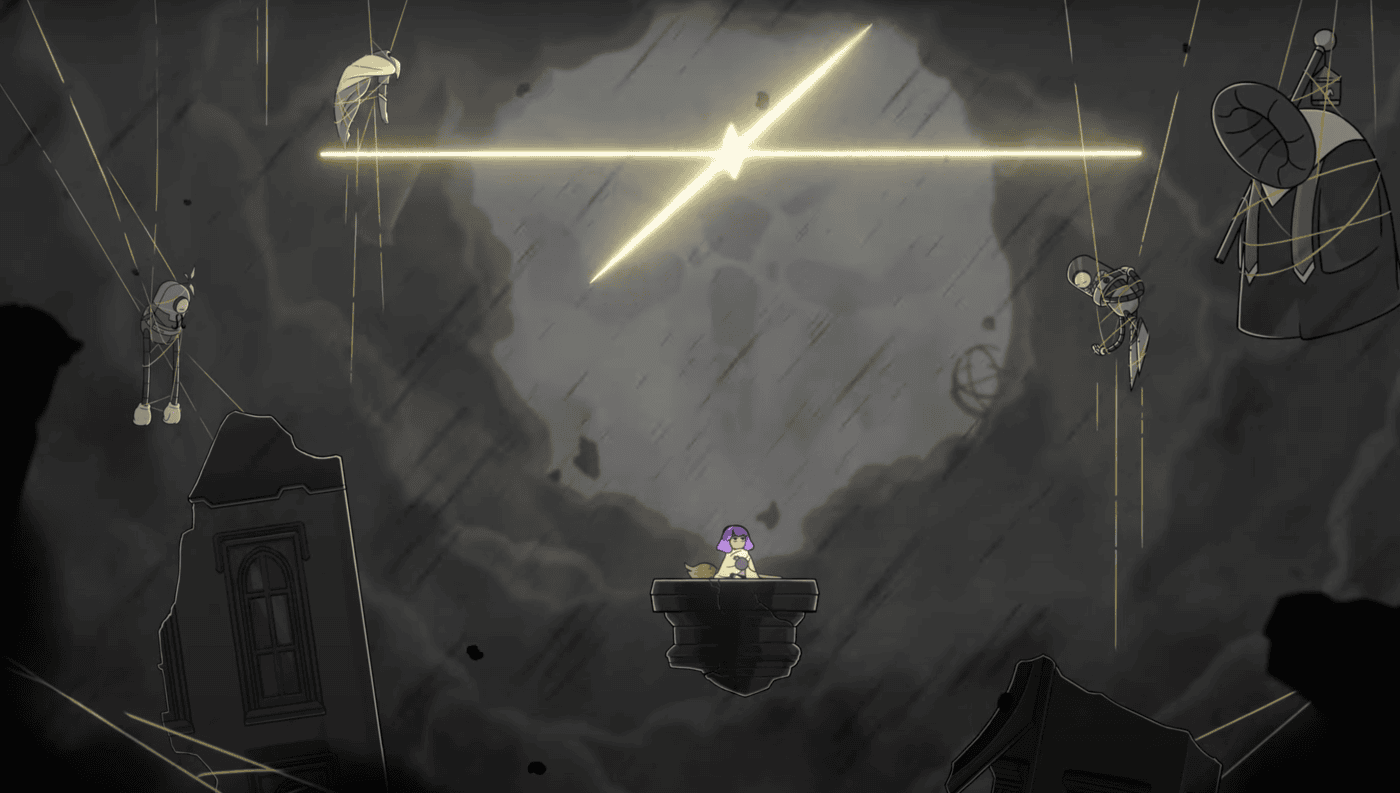

Sebastian: For this one, I think I actually have a good answer, haha. It’s really a combination of both. We definitely rely on environmental storytelling — different characters and objects in the game represent experiences, memories, or conversations that Constance had in her real life. Because everything in this inner world is essentially part of Constance herself, nothing is random or disconnected. Everything you encounter reflects something she has actually gone through. So, there’s a lot to piece together if you’re paying attention.

But on top of that, we also have a very specific narrative layer that kicks in at key moments — without spoiling too much, let’s just say that defeating certain major bosses or reaching important milestones triggers a unique storytelling system. These moments let you interactively uncover more about the real-life Constance and what led to her current state. They’re more direct, but still open to interpretation. We’re not spelling everything out, but there is a clear emotional and narrative thread we want to communicate.

It’s a structure I haven’t seen in other metroidvania or action platformers, and I’m really curious how people will experience it.

Before delving into the many layered themes woven into Constance, we’d like to pause for a more intimate reflection on the role and symbolic power of painting within the game. Could it be said that, for the young protagonist, painting serves as a form of therapy — a restorative act through which each brushstroke brings color and life to a world weighed down by sorrow? Might this creative expression serve not only as a path toward healing her fractured psyche, but also as a way of mending the decaying inner world in which she is, in many ways, confined?

Sebastian: We definitely have a recurring theme around paint as a force for reconnecting and restoring the broken world — there’s that symbolic layer, for sure. But to me, the heart of Constance’s journey lies in self-discovery. Her creative tools, her brush and the powers that come with it, aren’t about fixing everything around her — they’re about helping her begin to understand herself.

She starts from a really low point, a place of emotional and creative stagnation. And what’s crucial for us is that this story doesn’t magically “heal” her. That would be dishonest. Mental health doesn’t work like that — you don’t go on a ten-hour journey and come out the other side perfectly fine. So, while there is restoration in the world and she helps others along the way, those moments don’t equate to her being fully okay.

Instead, this is the beginning of something. It’s about becoming aware — about recognizing what’s broken, both outside and within. Awareness and acceptance are the real milestones in this story. And in that sense, you mentioning therapy is very accurate. In a way, reaching the point where Constance could even consider starting therapy — that kind of self-awareness — is the goal of this narrative.

Constance, through a unique and deeply personal lens, invites players to embark on an intimate journey into the realm of mental health—exploring the painful yet necessary process of confronting, processing, and ultimately healing from trauma. And this is just one of the many timely, nuanced, and emotionally resonant themes intricately woven into the game’s expansive world and the labyrinthine depths of Constance’s subconscious. Without venturing into spoiler territory, could you share which other major themes will lie at the heart of this psychological odyssey through the mind of our young, paintbrush-wielding artist?

Sebastian: We definitely touch on themes like anxiety and depression — but it’s really important to us that we never explicitly use the word depression in the game. We’re not psychologists or therapists, and we’re very aware of that. What we can speak to is our own lived experience — and that’s where the story comes from: it’s deeply personal, and at the same time, shared.

While Constance’s journey started from my own personal creative and emotional struggles, it quickly became clear that everyone on our team — we’re a small group of about eight people — had their own mental health story to tell. That naturally fed into the development of the narrative and characters. So even though we avoid clinical labels, the emotional beats are inspired by real moments that we’ve all experienced.

Some of the themes we explore could be described as “mental health adjacent” — things that affect our inner world but aren’t always labeled. For example, imposter syndrome comes up, and so does the feeling of being caught in a kind of thought carousel — when your mind is so restless and overloaded that it becomes paralyzing. I’m sure there’s a clinical term for it, but that’s not really the point — what matters is that these are experiences we’ve had and wanted to reflect in the game.

We also touch on support systems — or the lack of them. Relationships, friendships, sibling dynamics — how those can shift, fracture, or be tested during difficult emotional periods. So even though Constance started as one person’s story, it evolved into something much more layered, with traces of all of us in it.

This may be one of the more predictable questions you’ll hear from us today, but it’s one we simply can’t avoid—precisely because it speaks to one of the very souls of the project. We’re referring, of course, to Constance’s stunning, frame-by-frame, hand-drawn 2D art direction—a visual style that doesn’t just define the game’s aesthetic, but breathes into it a unique soul, identity, and emotional depth. It brings the world and its characters to life in a way that feels both timeless and intimate — reminiscent of the wonder we felt as children, leafing through the pages of a beautifully illustrated storybook. Could you take us inside the creative journey that led to this artistic choice, and how it gradually shaped into what we now see on screen? And if we may add—beyond your vivid imagination, was there anything in particular that served as inspiration or artistic compass along the way?

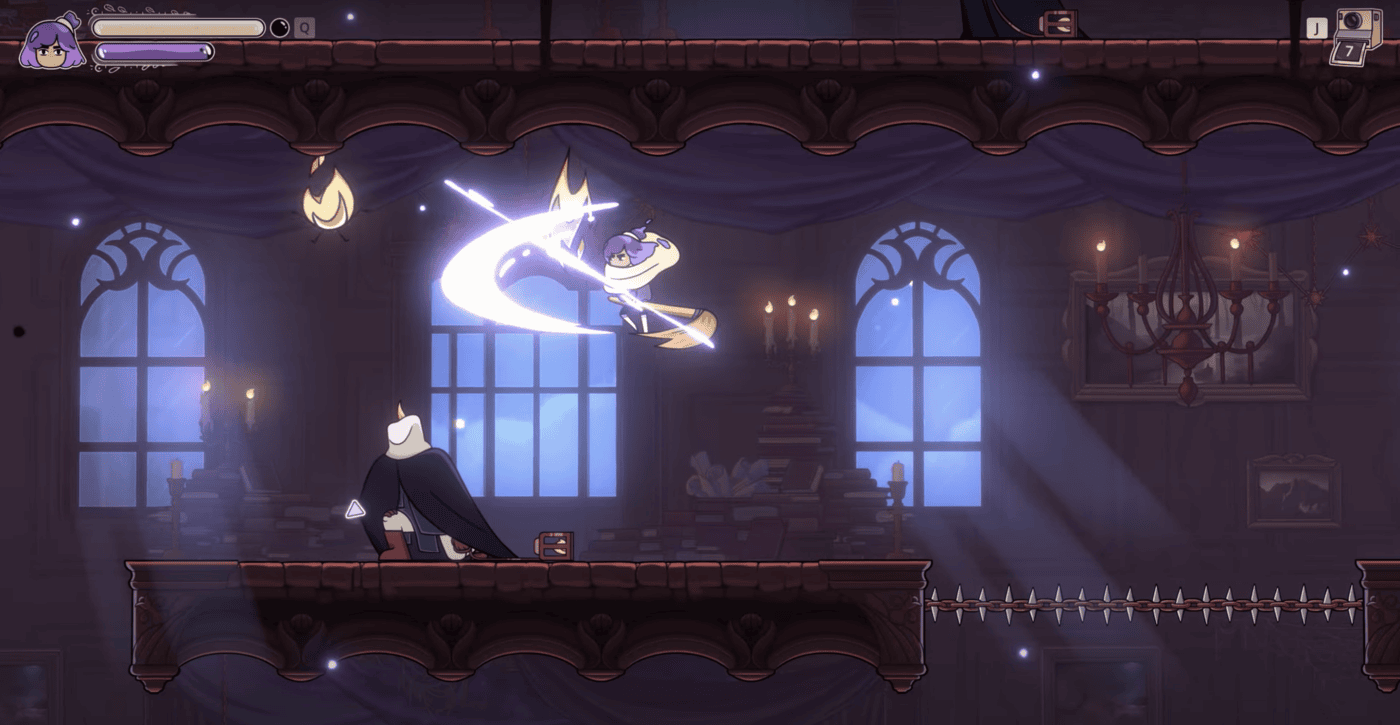

Sebastian: Our main animation inspirations definitely include Hollow Knight, Celeste, and Ori. Even though their art styles are very different, what they all have in common — and what really impressed me — is their incredible sense of animation fluidity and character feel. Hollow Knight, in particular, stood out to me. It uses a surprisingly minimal number of frames, but never sacrifices motion quality — everything just flows. That kind of efficiency and expressiveness was a huge influence on us. I knew I wanted that kind of hand-drawn fluidity for Constance.

We were really lucky to find Sunitha, our 2D character artist and animator. After searching and interviewing a lot of people, she just instantly stood out. She’s an absolute force of nature — incredibly talented and with a really strong creative identity. She’s the one who truly brought Constance to life. Not just in terms of animation, but in design, in shape language, and ultimately in personality. She made Constance her own.

What’s so special is that she has this deep need to animate everything with a ton of care and detail — she doesn’t like cutting corners. Even in simple idle animations, there are a lot more frames than you might expect, because she wants it to feel alive and fluid. And that energy fits Constance perfectly — especially with the brush and the paint, which flows and reacts and breathes. Sunitha’s animation style ended up shaping the entire visual identity of the game. You can really feel her hand in every frame.

If you combine Sunitha’s character and animations skills with the environment art skills of our artists Siba and Viki you get the full artstyle for Constance. They love the world that they are creating, they are super into little narrative moments and worldbuilding scenarios that they create with the help of the tiniest little details in their environment art. The most fascinating things is that none of the three ever worked on a video game like this – truly amazing.

While Constance—much like Trüberbrook before it and the upcoming The Berlin Apartment—makes it immediately clear that art is a central motif and one of the core driving forces behind your creative process, what truly fascinates us is the bold shift in approach between your debut title and this latest project. You’ve moved from a 3D, story-driven point-and-click adventure rooted in a more traditional gameplay formula to a 2D action-adventure experience built around a Metroidvania-style structure and a very different philosophy of player interaction with the game world. Could you tell us more about what inspired this dramatic change—not only in terms of game design, but also from an artistic and gameplay-perspective standpoint in shaping the overall vision for Constance?

Sebastian: That one’s actually pretty simple to answer. Constance wasn’t developed by the same core team as Trüberbrück or The Berlin Apartment. I joined the Games Department later, after those projects had already been made or were in development. So, Constance really came in from the side — it’s not an evolution or continuation of those earlier games.

Most of the people who worked on Trüberbrück also went on to work on The Berlin Apartment, so you can see a more direct line there in terms of creative progression. But with Constance, I brought my own idea and my own direction into the department. It’s more like a parallel path that happened to emerge within the same company, rather than something that evolved out of the previous projects.

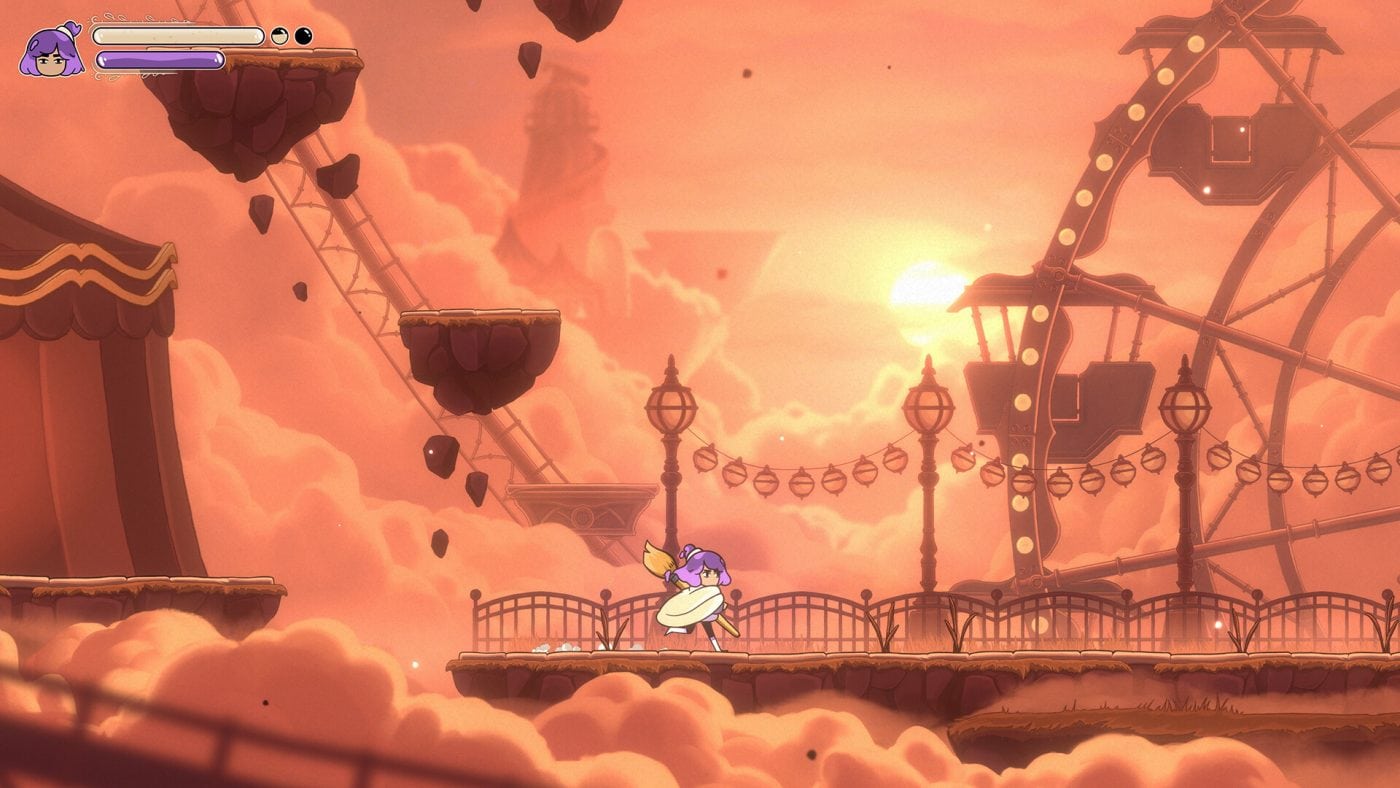

Constance is set to land on digital shelves in Q4 2025—a release window that will see it go head-to-head with some of the most anticipated titles in the Metroidvania subgenre, including the long-awaited Hollow Knight: Silksong. Yet it comes armed with a truly captivating ace up its sleeve—one we’ve already touched on in earlier questions: the ever-present companion of our paintbrush-wielding protagonist—her brush. Far more than a mere tool, it acts as a powerful extension of self, a vessel of expression and imagination, capable of breathing life into the world as well as crafting art. With that in mind, we’d love to hear more about how this unique mechanic shapes the heart of the experience. Could you give us a brief overview of the gameplay and share how Constance sets out to carve its own distinctive space within the increasingly crowded Metroidvania landscape? More specifically, how do you envision the brush’s unique abilities reshaping core pillars of the experience—from exploration and environmental interaction to platforming and combat mechanics?

Sebastian: Yeah, the brush in Constance is a bit like the needle for Hornet — it’s our core identity. It’s not just a weapon, but the central mechanic for everything you do in the game. What really sets Constance apart from most Metroidvanias is our strong focus on precision platforming. That’s where the influence of Celeste comes in. Of course, we still have exploration and combat — it’s a metroidvania after all — but the feel of the gameplay is quite different.

You could almost think of Constance as a kind of open-world Celeste. You’re navigating a metroidvania structure, but inside that are handcrafted platforming segments that have the tight, skill-based challenge of a Celeste level. That’s something very unique to us, and it actually influenced how we designed things like the game over and reset systems. We knew we couldn’t mix precision platforming with frustrating backtracking — that would kill the flow completely.

Another thing that makes Constance distinct is that every brush ability you unlock is used across all aspects of gameplay — platforming, combat, and puzzles. That gives the tools real depth and keeps the experience cohesive. Some biomes lean more into puzzle-platforming, others have more classic puzzles.

So yeah, that combination of precision platforming in a metroidvania world, layered mechanics, and our unique narrative mini-games makes Constance something really fresh, even in a genre full of amazing games.

Taking into account everything we’ve touched on so far—from the core gameplay pillars, including the main narrative arc and optional side quests, to the pacing and degree of freedom players may choose to exercise in exploring the world—roughly how many hours do you anticipate the full experience will span? Both for those following the main storyline and for completionists determined to uncover every secret the game has to offer?

Sebastian: This one is so hard to answer haha, because current testers’ times vary a lot. I’m guessing 8-10 hours of average time for the completion of the story could be realistic. All challenges, side quests, upgrades & collectibles might bring you up to 12-14 maybe. But again these are SUPER rough estimates haha. There might be expert players who might be able to rush through in 6-7 hours, but that would be REALLY impressive for a blind run – and there might be slower players who explore really thoroughly and that just take their time and they might and up with 20 hours. I’m actually very curious about that myself.

Another standout feature of Constance—one that naturally draws our attention—is the way it approaches character death and the resulting freedom granted to players in choosing how to respawn. As outlined on the game’s Steam page, upon death, players are given the agency to decide how to proceed: push forward through adversity at a cost, or retreat to a safe point and chart a different, unexplored course. With that in mind, we’re curious—just how central is this mechanic to the overall game design and player experience? How might these decisions shape or reflect Constance’s emotional and psychological journey? And ultimately, will the choices players make in the face of death bear meaningful consequences that influence the narrative arc or lead to different possible endings?

Sebastian: Yes, like I mentioned earlier, our game over — or as we call it, the persevere system — is actually a core part of our level design, pacing, and even how we place meditation points, which are essentially our save spots. We really see this mechanic as one of our unique selling points because it directly addresses something many players dislike: badly designed or tedious backtracking.

Constance is designed to be a much denser experience — heavily inspired by Celeste in that regard. There aren’t dozens of empty rooms or filler areas. Almost every screen or space has something going on: platforming, combat, puzzles, secrets — it’s all very intentional. So the persevere system ties into that tightly. It keeps the momentum up and makes sure that failing doesn’t feel like a punishment, but part of the rhythm of progressing.

This system has gone through quite a few iterations. The first demo had one version, the second already evolved it significantly, and now as we’re getting close to release, we’ve arrived at something that feels really special. Without spoiling anything, I can say this new version does things in a way I haven’t seen in other games, and we’re very excited to see how players respond to it in testing.

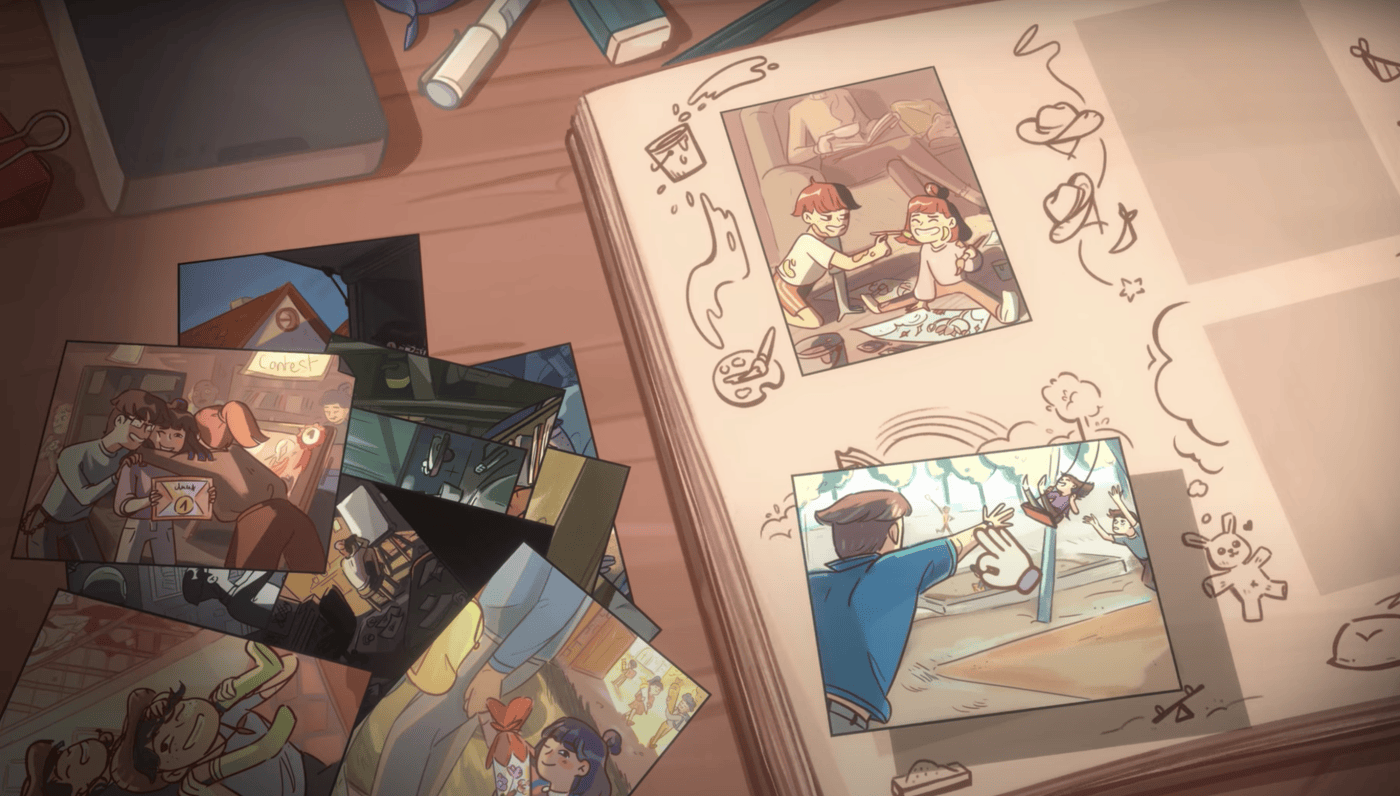

Character progression is a cornerstone of any Metroidvania, and in Constance, players will shape their development by collecting scattered “inspirations” hidden throughout the world—artistic fragments that can be sketched into Constance’s personal journal to unlock, enhance, and tailor her abilities. Could you walk us through your vision for this progression system? Specifically, how is the journal woven into the gameplay experience, and what role does it play in deepening player customization, agency, and overall immersion?

Sebastian: The inspiration system and the journal were actually there from pretty early on in development. We always imagined Constance carrying a sketchbook rather than a traditional journal — something that feels more personal and expressive. The journal is part of that sketchbook, where she notes down her main experiences — things like story beats or quests. Then we have additional pages, like the character section, the map, and of course, the inspirations page.

The inspirations system is our unique take on fusing something like Resident Evil’s inventory management with Hollow Knight’s charm system — but with a fresh twist. Each inspiration is kind of like a Tetris-shaped sketch you place on the inspiration page. Once placed and “drawn,” it grants Constance various abilities or buffs. This lets players tailor their playstyle — whether they want more aggressive tools, defensive support, paint-saving mechanics, or something more experimental.

On top of that, sketches can be upgraded with color, turning them into fully realized artworks. That process doesn’t just change the visuals — it also powers up the ability itself. So if you really connect with a particular ability, you can invest in it, enhance it, and make it central to your gameplay experience. It’s all part of reinforcing the theme of creativity — where your choices, your style, and how you express yourself all directly impact how you play the game.

Let’s delve into one of the most compelling elements of Constance: its magical yet melancholic inner world and the strange, symbolic beings that inhabit it. Through the intricate details woven into each of the game’s six biomes—a delicate yet deliberate balance—the environment and its creatures appear to embody vivid reflections of both abstract emotions and concrete memories from Constance’s personal history. To what extent can these biomes—with their distinctive aesthetics, architectures, and eccentric inhabitants—be interpreted as manifestations of past traumas in the life of the young, paintbrush-wielding artist? Or are they more accurately reflections of her emotional landscape, inner turmoil, and the beautifully ordered chaos of her creative mind?

Sebastian: Each main biome in the game is centered around a mentor — a character inspired by real-life artists who represents a specific facet of Constance’s mental health journey. These mentors aren’t just guides; they each embody a part of the emotional weight or internal conflict Constance is carrying.

By helping these mentors through their unique personal struggles, Constance gradually uncovers the root causes of her own decline. Each biome, through its visual identity, mechanics, and story, reflects a distinct emotional challenge — and resolving it reveals one of the key issues that contributed to where she is now mentally.

So in that sense, the mentors and their worlds aren’t just narrative devices — they are direct metaphors for the fragmented parts of Constance’s psyche. Helping them is, in essence, helping herself take the first steps toward self-understanding.

Before we move to our final question, we’d love to take a moment to delve deeper into your vision for the game’s artistic soundtrack. So here’s a direct yet meaningful one: how did you approach the composition of the game’s original score? What instruments, sonic textures, and compositional choices did you employ not only to narrate her journey through music, but also to evoke the emotional spectrum, tonal subtleties, and the inner palette of Constance’s psyche?

Sebastian: The worlds of Studio Ghibli were a very direct influence for us—especially in terms of music. Ghibli scores do an incredible job of balancing a nostalgic, melancholic tone with beautiful, memorable melodies that evoke hope. And hope is a central theme in Constance: the belief that you can move forward, that things can get better, and that you’re not stuck in the dark forever.

Our composer, Tiago, is also a huge Ghibli fan, which made things click immediately. He deeply understood the emotional undercurrent we were aiming for and was able to translate that into sound.

We experimented with a lot of musical approaches—different instrumentations, varying levels of orchestral scale, and even the inclusion of electronic elements. We asked ourselves: should it feel big and cinematic, or intimate and close? Should it have electronic undertones in certain worlds? In the end, we decided to keep things grounded. This is a very personal, emotional game, and we felt the music should reflect that intimacy.

So we landed on something closer to a small ensemble—almost like a quartet. Few instruments, but each with purpose and emotional weight. In key moments or certain biomes, we allow a bit of subtle electronic influence or synth textures to come in, but they never dominate. They just gently enhance the mood, keeping everything cohesive while still allowing variety.

It’s all about making the music feel like an emotional companion to Constance’s journey—supportive, evocative, and human.

As mentioned earlier, Constance is scheduled to launch in Q4 on PlayStation 5, Xbox Series, Switch, and PC via Steam, in partnership with publisher ByteRockers’ Games. Have you set a specific release date yet? Furthermore, could you outline the key milestones and next steps on your roadmap as you approach the launch?

Sebastian: By the time this interview is released, we will have already announced our planned release date: November 24th, 2025, for PC on Steam. We’re really excited to finally share that with everyone. The console versions are absolutely still in the pipeline, but they won’t launch simultaneously—we’re aiming to bring Constance to consoles in 2026, hopefully not too long after the initial release.

Right now, our team is fully focused on hitting key marketing milestones. We will have just premiered our release date trailer during the Future Games Show, and we’re also going to be part of Steam Next Fest this October, which will be a big opportunity for us to connect with players and build momentum. We’ve got a few more things planned in the lead-up to launch—some exciting beats we’re hoping will help set the stage for a strong and meaningful release.

Pick up your brush, open your heart, and let Constance lead you through the vibrant tapestry of her inner world

And that’s all for today.

But don’t worry—this is only the beginning. We’ll be back soon to uncover more of the long, winding odyssey that awaits Constance within the hidden chambers of her fragmented mind.

Before we part ways, allow us—as always—to express our deepest thanks.

First, to you, our readers, for joining us on this journey and sharing in the experience.

And most importantly, to Sebastian, for offering us this opportunity and guiding us—like a modern-day Virgil—through the rich, multifaceted world of Constance.

Constance will launch on PC via Steam on November 24, 2025, with console versions to follow.

To stay updated on the latest news and developments, be sure to follow the game on social media, visit btf’s official website, and join the Discord community to connect with fellow adventurers.

And in case you missed it, you’ll find the official release date trailer below—unveiled by btf Games and ByteRockers’ Games during the Future Games Show.

Enjoy the trailer—and stay tuned. There’s still so much more to discover.